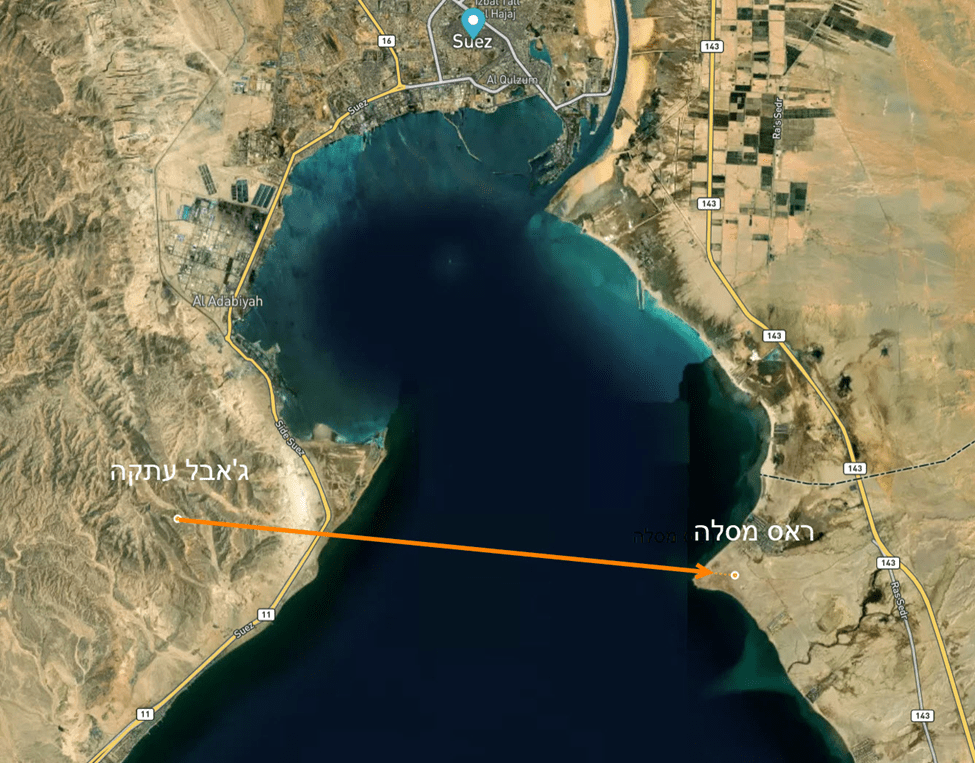

In recounting the fall of the Mezach(quay) outpost in the Yom Kippur War, people always mention the attempt by the fighters of Unit 707, escorted by three Dabur patrol boats, to free the soldiers trapped there — an attempt that ended in failure. The Daburs reached a point south of Ras Masala, and the rubber boats advanced until they were spotted. Then, 130-millimeter guns from Ras Mahgara opened fire, forcing the entire force to retreat.

Shells fell between the rubber boats and the Daburs. The sea — merciful for once — slowed the shrapnel in the water, so only minor damage was done to the vessels. By some miracle, there were no casualties.

Someone saw fit to blame Ami Ayalon, claiming that he gave the radio order for the rubber boats to open up their radar reflectors, which allegedly revealed their position. I once asked Ami about it. He told me that the order had been part of the operational plan, as presented and approved by headquarters in the mission briefing. I have every reason to believe him.

And if we’re already speaking of Ras Masala and the guns of Ras Mahgara, there is another story that has stayed with me ever since the War of Attrition.

On the afternoon of August 13, 1969, IDF soldiers were relaxing and swimming in the turquoise waters off Ras Masala. They felt no fear of the Egyptians; they believed the enemy’s artillery could not reach them — “out of range,” they said.

Here is my conjecture:

Not long before, the Egyptians had received radar-guided 130-millimeter artillery pieces from the Russians and had positioned them on Jebel Ataka — known to sailors as Ras Mahgara. Although these same guns had already been used a month earlier in the battle for Green Island, Israeli intelligence had not yet updated its estimate of their range. That day, the Egyptians decided to test their new weapons and began a heavy bombardment on Ras Masala.

Or perhaps it was revenge — a retaliatory strike for the Green Island raid that had humiliated them only weeks before.

Until that moment, the scene was idyllic: a canteen truck parked on a golden beach, the blue sea dotted with young soldiers, some of them in swimwear. Then, in an instant, paradise turned into hell.

Mutilated bodies lay unrecognizable, and soldiers with severed limbs lay on the soft sand as their blood soaked the cursed soil of Sinai. On land there was no forgiving sea to slow the shrapnel — only the angel of death, drunk with fury, swinging his sword.

The gold turned crimson.

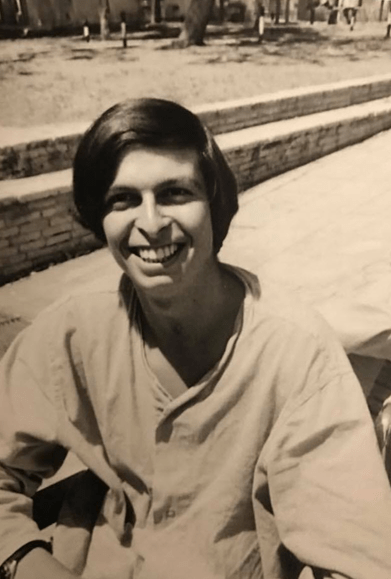

Twelve IDF soldiers were killed on the spot, and many others wounded. Among the severely injured was my classmate from the ORT high school in Rehovot — Miki (Menachem Yitzhak) Mushinsky of Kfar Mordechai, near Gedera, who served in the Signal Corps. At first, he was placed among the dead, but later a doctor decided to load him onto the evacuation plane — a faint hope that he might survive.

I made it a ritual to visit him at Tel HaShomer Hospital whenever I came home for the weekend from the naval training base. My first visit I will never forget.

It was Friday. I, Jacob Bogatch, dressed in the crisp Dacron uniform of a newly minted naval cadet, came to see my wounded friend.

I found him in a ward filled with amputees. The air was thick with the stench of burned and rotting flesh. Blood-soaked bandages wrapped around fresh stumps, some still exposed. The building, a relic from the British Mandate, had seen much in its time. Around me lay rows of wounded soldiers — some groaning in pain, others silent, lost in the haze of morphine. The smell lodged itself in my nostrils and followed me for days.

At first, I felt as though I had stepped into a scene from a World War I film. But this was no movie. This was the unvarnished reality — no actors, no extras. My friend, born barely two weeks after me, with whom I had stood at our high school graduation only a year before, now lay before me, tormented and broken, fighting for his life. Around him lay others, their faces twisted in agony, their world reduced to pain and despair.

I was in shock. My breath grew shallow, as if my soul were trying to flee my body. I couldn’t take it in.

Outside, the sun shone as usual, and in the streets of Israel there was no trace of the war raging on the western edge of Sinai — nor of the battle fought here, under this roof. I thought, with what reason I had left: perhaps that is how it is when horror stays out of sight. But nothing about it seemed logical.

Unimaginable — that the friend I had always known for his wide, radiant smile now lay before me, both legs gone, one arm shattered, his face twisted with pain. I stood beside him trembling uncontrollably, unable to utter a word of comfort. When the tears came, I turned and walked out.

Outside, my stomach churned, and a silent cry tore from deep within me toward the heavens.

Why?

I wept all the way home. That day I saw, with unbearable clarity, the true face of war — the misery it brings, the pure lives it destroys.

When I could think again, I began to question the order of things. I had fought hard at the recruitment center not to be assigned a desk job. Because I was an electronics technician, they wanted me in the rear; instead, I volunteered for the naval officers’ course. My friend, also an electronics technician, was sent to the Signal Corps — and on a day of rest, he nearly lost his life.

Was it luck? Or judgment? At nineteen, I had no answer.

From that day, the hardships of the officers’ course seemed to shrink to nothing — mere games, youthful challenges, adventures sprinkled with mischief.

From then on, I let life carry me, like a leaf torn from a tree and swept along by the rainwater — sometimes caught against an obstacle, only to be freed again by the current. And so, I drifted through the rest of my service, carrying on my back the burden of that visit.

I continued visiting Miki until I no longer could. Each visit demanded immense inner strength — more than I possessed. I watched the nurses tending to the wounded with tireless devotion, and I could not fathom where they found the strength.

Miki overcame it all with extraordinary courage. He recovered, built a family, graduated from the Technion, and made remarkable contributions in the field of electronics. He even founded the Israel–China Chamber of Commerce.

He passed away from a serious illness in 2016.

Miki (Menachem Yitzhak) Mushinsky — may his memory be a blessing.

Miki in his childhood wanted to be a seaman also he lived near Gedera

That big smile. I’ll never forget

The measured distance on the map between Jebel Atka and Ras Masalah is 17 km, which is the end of the effective range of the 130 mm cannons

Leave a comment