Once, before we even dreamed of digital notebooks, we carried small notepads in our shirt pockets to serve as our secretaries — ones that wouldn’t let us forget what we needed to do.

As a young Dabur commander (873), I opened such a notebook and jotted down details that I’ve long since forgotten. Now, after searching through my memory box, the notebook reminded me of things I’d completely forgotten — and at times, I can’t believe it was me who wrote them.

Unfortunately, I didn’t think to date the pages — back then I didn’t see any of it as historical material.

Photo #1

The cover of the notebook — surely anyone who lived during that time remembers it.

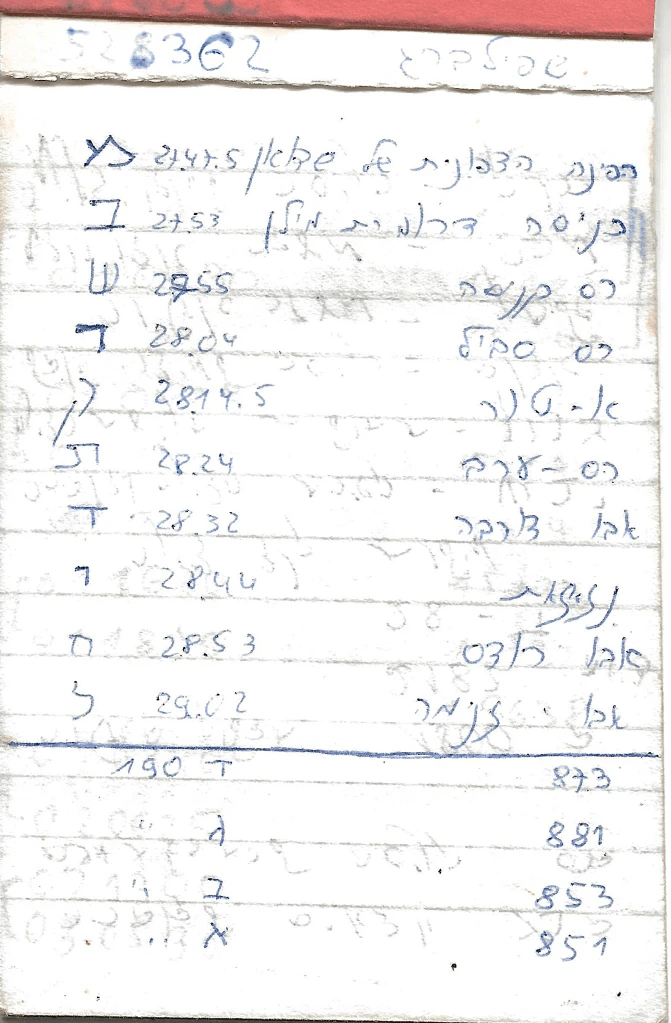

Photo #2

At the top, for some reason, is the name and phone number of Spielberg. (Note how back then phone numbers had only six digits — and that was just fine.)

Since this number doesn’t match Hollywood phone numbers, I assume that at the time, I knew someone named Spielberg — a woman, likely important to me. Her number appeared at the top of the notebook, on the page stub, so I couldn’t tear it off.

Below that are the details of an important mission in which we escorted an oil-drilling barge from the Red sea across from the port of Aradkah in Egypt to Abu Zenima. The barge had arrived from Holland after circumnavigating Africa in a continuous voyage. A previous attempt to transfer such a barge had failed — it stopped en route and was sunk by terrorists near South Africa or Spain (I can’t recall exactly). This time, Israel sent four Dabur boats for escort as the barge entered the range of Egyptian coastal artillery. The barge made it safely to Abu Zenima after a three-month non-stop voyage, unloading about a dozen tired and, frankly, extremely horny crew members.

As for us Dabur crews, we just had to be careful not to bend over or turn our sterns toward them.

The list contains codewords for radio communications.

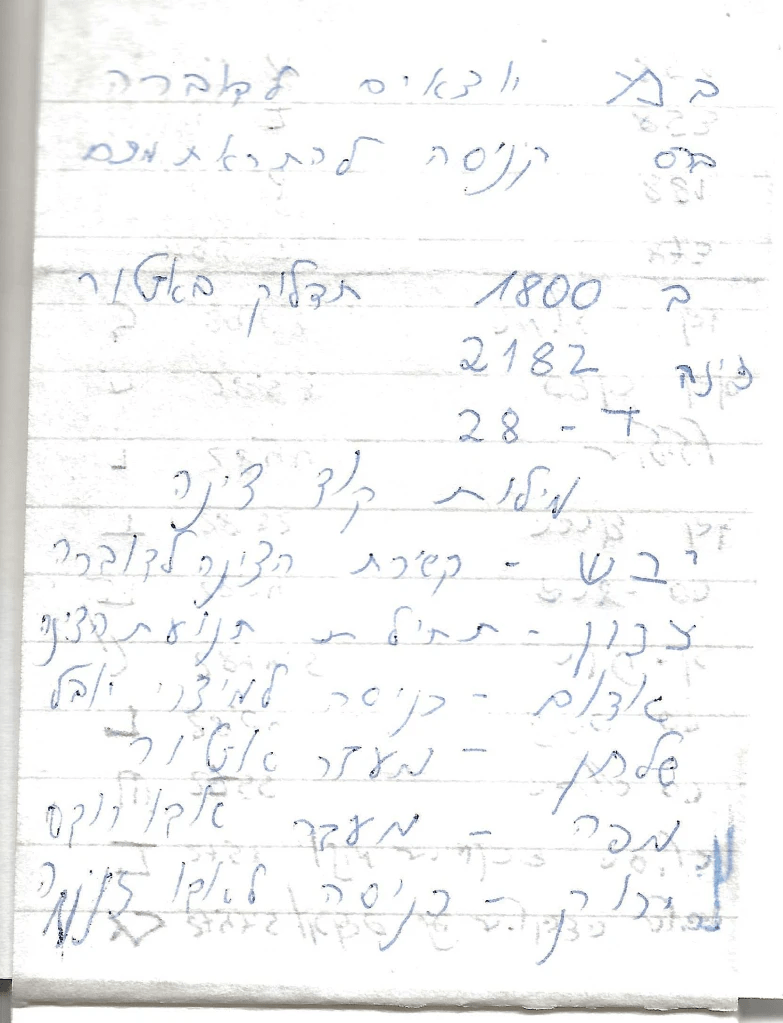

Photo #3

More codewords for mission phases.

The Tzina was a tugboat from Eilat that sailed to a point south of the Jubal Straits to replace the Dutch tug and tow the barge through the turbulent Suez Gulf.

I knew the Tzina personally — it was the same tug that came from Eilat when we (873 and 851), two Daburs, ran aground on reefs/islands in the Tiran Straits. It nonchalantly pulled us back to Eilat.

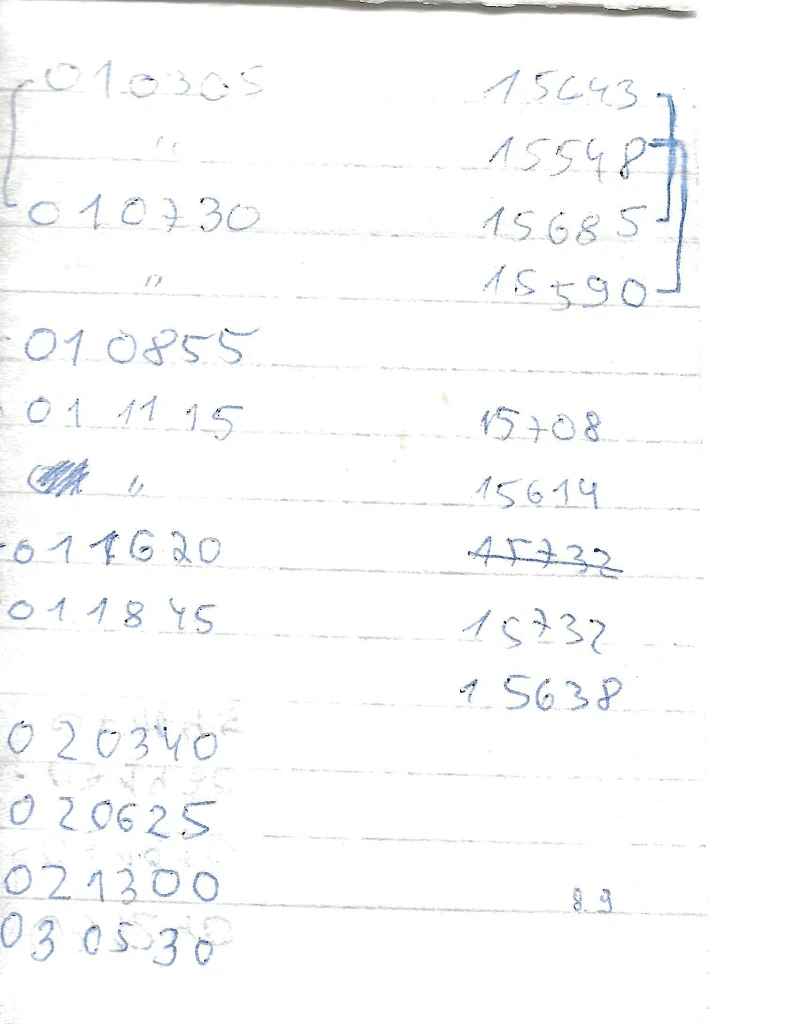

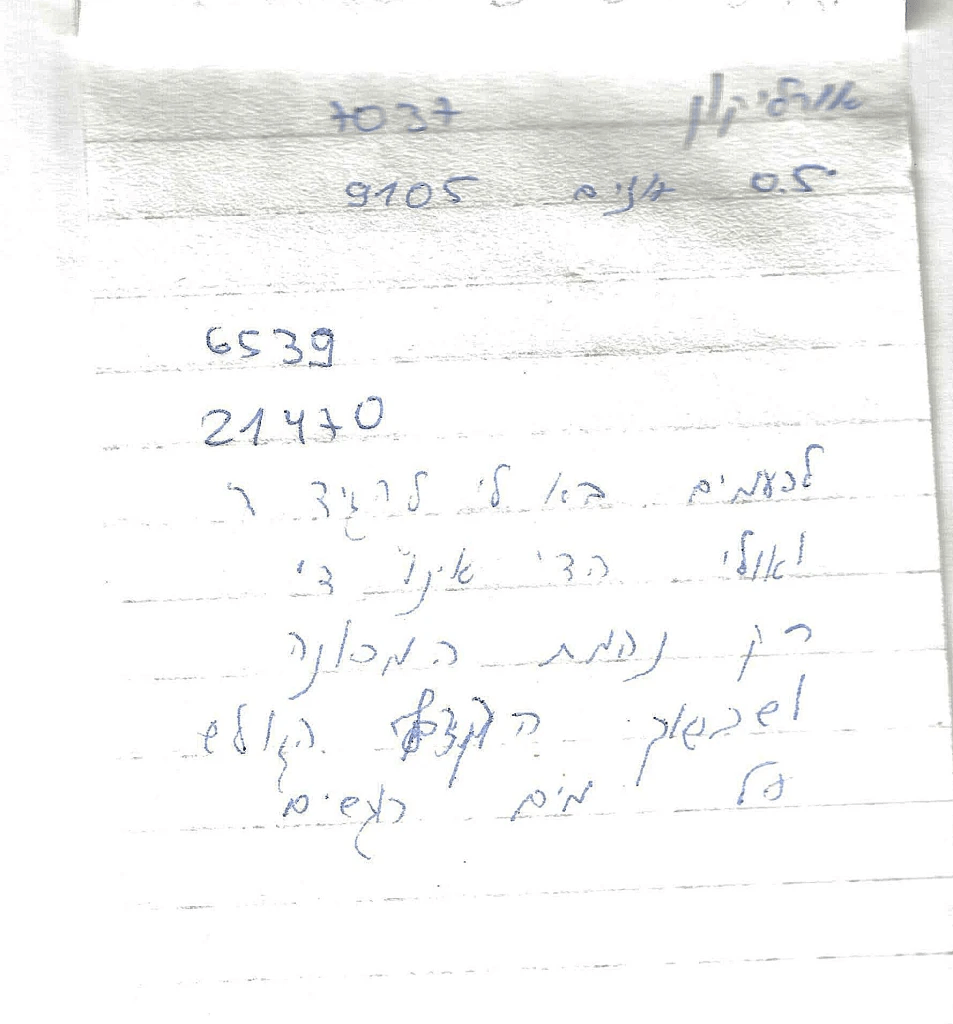

Photo #4

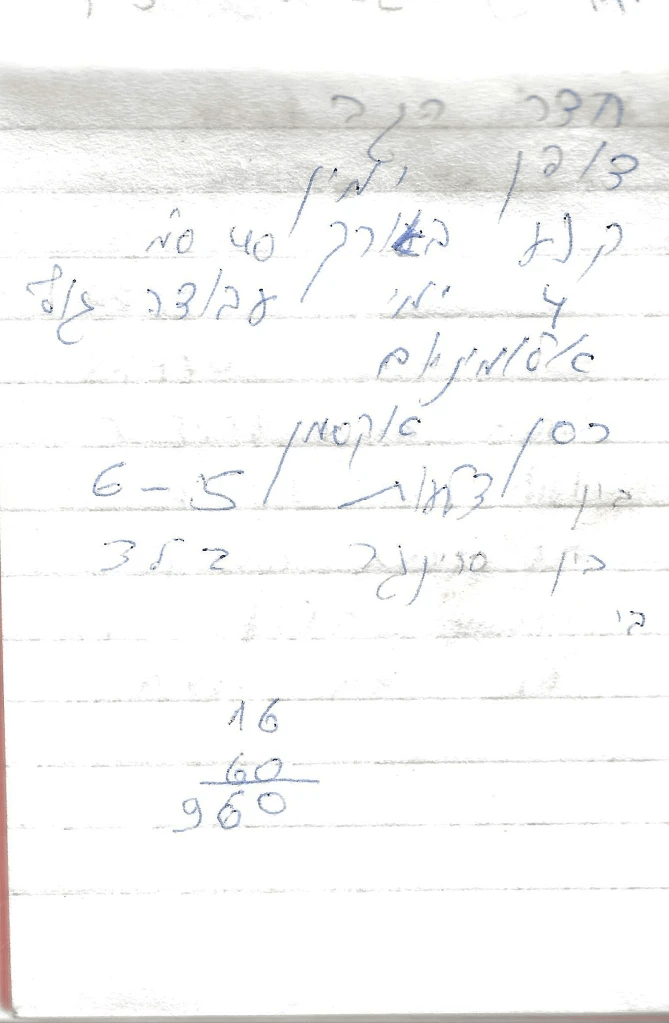

This jumble of numbers reminds me of only one thing: chart updates.

Back then we had to update the ship’s nautical charts by hand, and the place to do this was the MZAR (naval logistics HQ) office “Karish.” Its head clerk, Sarit, ran the office like a pharmacy (they didn’t call it a “bureau” yet; that happened later when “Karish” was replaced). Her charts, along with the intelligence files, were always up to date. When it became a bureau, the “pharmacy” turned into a whore house — and we could no longer update anything. But we could do something else with our hands.

Photo #5

Crew list for boat 873 (not in my handwriting).

For some reason, I added the name of Dudu Ben Ba’ashat (he was class 19, I was class 18). Maybe he was an attaché trying to join Flotilla 915.

Photo #6

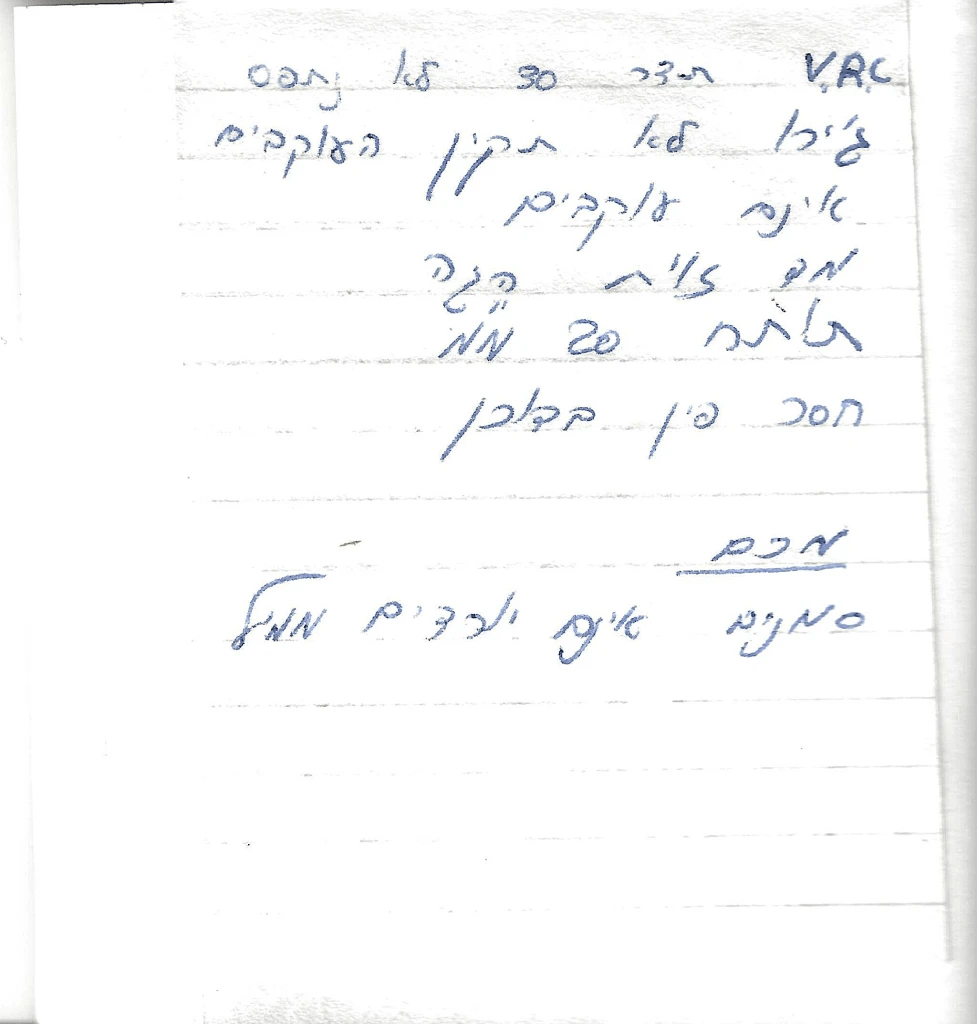

No notebook is complete without a list of malfunctions, and no malfunction list is complete without a broken radio, gyro, 20mm cannon, or radar.

Photo #7

We spoke on the radio using codewords. Sometimes I had to write down what I wanted to say in the notebook before speaking, so I wouldn’t mess it up.

Photo #8

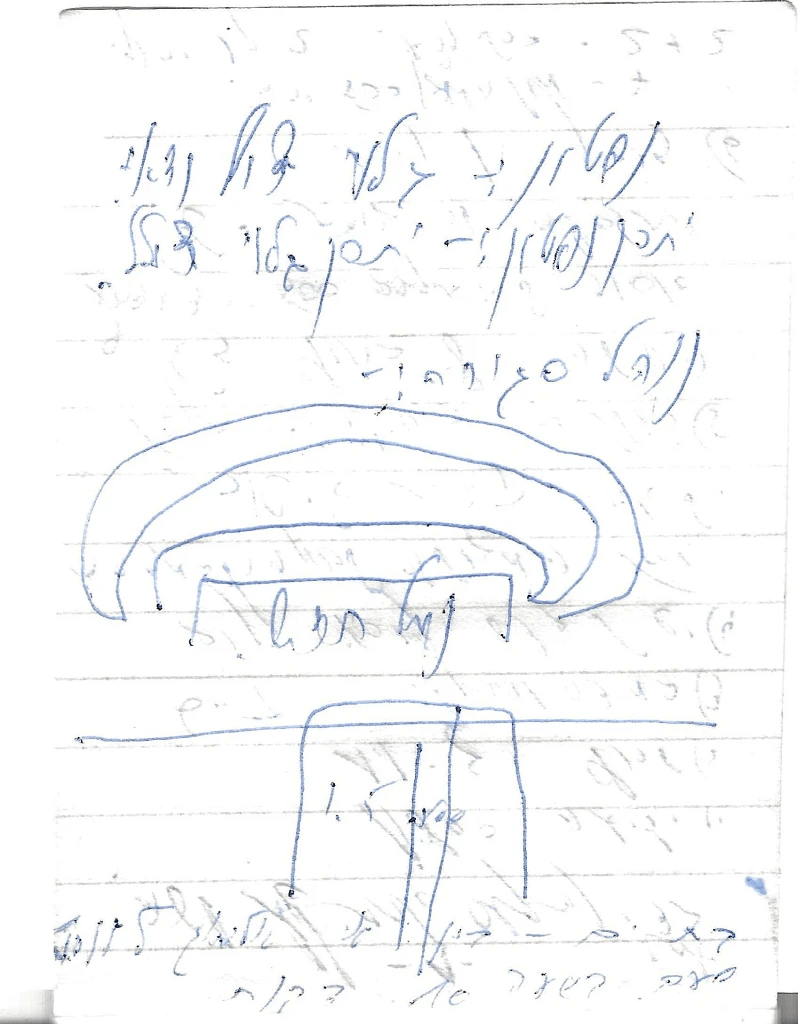

Apparently, during a briefing, Ami Ayalon didn’t have a notebook, so he wrote in mine — details of a secret operation near the Port of Eilat, including execution instructions. I don’t remember whether it was during battle exercises or if there was genuine concern about Egyptian divers planting mines in the port, possibly from Jordan. I’m sure no mines were laid during our watch — not then, not ever.

Ami made us feel like every task was part of a mission to capture another post atop the fortress on Green Island. We really felt great around him.

Reading this brought back memories of that mission.

We completed it and returned the next morning to the naval base in Eilat, heading straight for breakfast.

At the entrance, we received news that left us in shock:

11 Israeli athletes participating in the Munich Olympics were murdered by terrorists. (November 6, 1972)

My blood ran cold, and even the Tnuva Sour cream served with breakfast lost its delicate flavor — the one I remembered from my Taba training days.

We sat in silence at long tables. Slowly, the blood returned to my brain, and a quiet conversation began among those seated. Across from us sat a group of reservists. Names were exchanged — and to my surprise, I discovered the guy across from me was Yaakov Bogatch, a former player on the Navy’s soccer team — and he looked nothing like me. Had it been another day, I might’ve sung the song from the play Two Kunilemel:

“They say I’m not me, and if I’m not me, then who am I at all?”

Photo #9

Continuation of instructions and diagram of the Eilat port.

Photo #10

Code names for locations along the Eilat coast.

Photo #11

Code names for vessels we were expected to see or encounter during the mission.

Photo #12

Continuation of vessel code names.

Photo #13

Detailed description of damage I caused to the Dabur when docking on a cradle (primitive dry dock) in Eilat, with only one engine working. I wrote it down to report to “Karish” over the phone and request to be relieved of command — before I sank the entire fleet and left the Phantom (berthing barge) in Sharm empty. He didn’t accept it and said that only a rabbi from Zikhron wouldn’t run into such trouble.

I also recorded the name of Major Moshe Oxman (of blessed memory), who was in charge of the Eilat dockyard and greatly helped me fix the issue. In return for a few cans of sardines, the hardworking dock crew quietly patched the Dabur’s hull. Oxman left the navy and was killed in the First Tyre Disaster during reserve duty.

Photo #14

At the bottom of the page I found a few words I’d written that deeply moved me.

To understand them, picture yourself aboard a Dabur on a long “Montana” patrol.

You’re standing on an aluminum deck that changes angle, direction, and height with violent, random jerks. It’s doing everything it can to throw you overboard. You cling to whatever you can to resist this villain. You succeed once — but what about next time? Then it returns, with a new trick, trying again to fling you into the sea, just before you lose your footing. This continues, minute after minute, hour after hour.

You’re on the bridge, looking down to see what’s wetting your toes. The sealed bridge leaks through every crack and seam — cracks that let in sunlight or stay hidden. Green water pours over every surface, finding its way in — to your feet or the gap between your neck and shirt collar. From there to the crack of your ass is a short trip. Ouch — shivers.

Now the Dabur gives you a free lesson in wave theory. Water shifting across the bridge due to pitch and roll creates small waves that crash into other small waves. Because the motion is irregular, natural phenomena emerge — waves canceling or reinforcing each other. Your toes measure depth and redirect flow. And all the while, more phenomena form. You’re exhausted. You bow your head, hypnotized by the movement. Time slows. Sounds fade.

Boom!!! — a massive jolt returns you to reality. A massive wave ambushed our bow just as we were descending from the previous one. The crash was the sound of the bow hitting the wave — combined with the clang of a red fire extinguisher in the bow room, which had come loose and flew like a cannonball into the hull.

The strong among us stayed standing — soaked in Red Sea saltwater. The weaker lay in their own vomit.

Beyond the roar of the sea were the engines — and the stench of diesel and black smoke seeping into every pore. Some collapsed from the cursed combo of waves, fumes, and smoke.

Escapism at this point meant lifting your eyes to the beauty of Sinai and Egyptian shores — mountains, palms, golden sands, deep blue sea misted with white — like brushstrokes from a drunken painter. You’d see the oil rigs with their eternal flames, and the foamy wake of the Dabur. You’d feel in your soul and body what Galileo meant when shown the Dabur:

“And yet, it moves!”

In all this chaos, I approached the navigation table, found a dry patch, took out my notebook, and wrote what I was feeling:

“Sometimes I feel like saying, enough!

And maybe ‘enough’ isn’t really enough?

Only the engine’s roar

And the lapping foam

Over stormy waters.”

I scribbled on a page — long forgotten.

Attention, Attention

Ahead: the anchorage of El-Tor.

To our right, on the reef: a pilgrim ship bound for Mecca, its journey ended here.

Prepare to disembark!

Photo #15

Apparently, no notebook is complete without at least one page of names, addresses, and phone numbers of women I was interested in.

At the time, I was focused on dreams of whaling in Norway and logging in Alaska — maybe that’s why there are only two names in the notebook.

I blurred the names so as not to harm these women, even though more than 50 years have passed.

Leave a comment