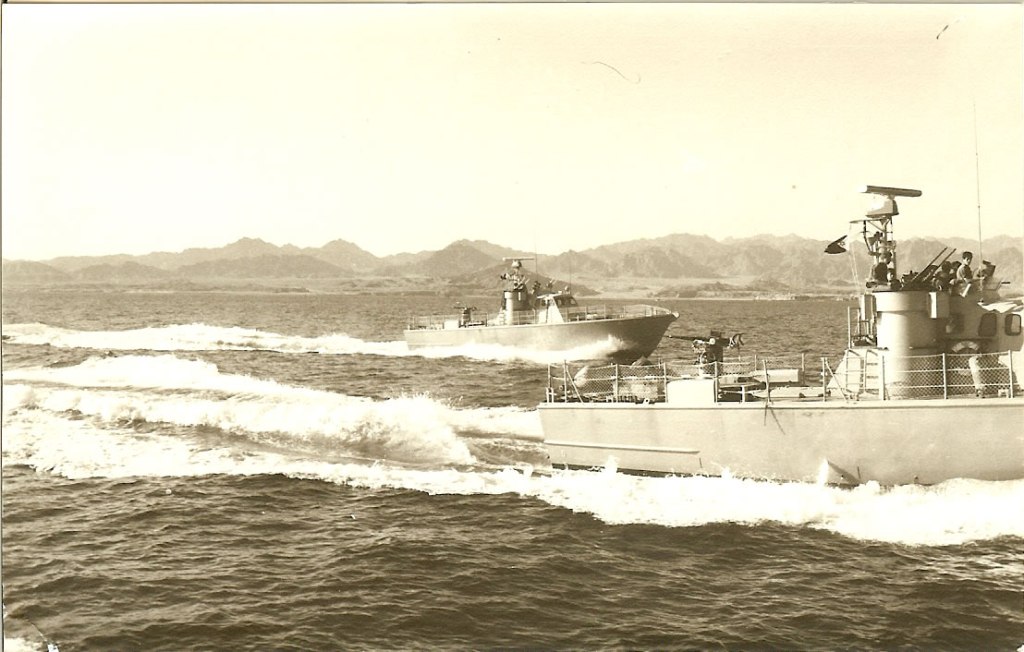

The voyages to patrol the Gulf of Suez, called “Montana” in military jargon, were carried out by pairs of Dabur boats through breathtaking landscapes. The combination of water, mountains, and sky left me speechless. The sea was often rough, with a 30-knot northern wind blowing for days on end, raising closely spaced waves that forced us to slow down to “hug speed.” Sometimes, sailing in high waves caused damage from the impact as we collided with the next wave. Beds were ripped off the walls, and the fire extinguisher turned into a missile flying through the cabin, searching for a victim.

Daburim sailing in the “triangular zone”

The phenomenon of current opposing waves due to tides was especially noticeable in narrow straits (like Jubal), where the current intensified. The same effect occurred when a landward wind blew and the opposing current was relatively weak, as in the area of El-Tor.

The high waves affected the crew as soon as the call ” Ship docking stations ” was made, still back in the quarters at Sharm. Muki started throwing up, followed by one or two more — was it from fear? From the smell?

As we departed, while still in the triangular zone (Sharem-Tiran Isl.-Rass Muhammad) with following waves, we conducted gun tests up to the turning point a bit south of Ras Muhammad. Turning west brought us into the real atmosphere: coral reefs to the right, opposite Shedwan Island and the Egyptian coast, waves still low but hitting the side. The turn to the northwest told the story of the voyage: stormy or calm.

We sailed to El-Tor (usually the first leg of the Montana voyage), passing through the Jubal straits, heavily influenced by currents. The wind was 30 knots from the north and had been blowing for days, creating high waves — with or without current. Today, looking at my charts, the tidal differences at Shedwan Island are about 2 feet, Ashrafi 1.8 feet, and El-Tor just one foot. Clearly, there was a current coming from the south every six hours, and I believe this current created the wave walls we faced. It’s a shame there wasn’t a commander with more Blue-sea sailing experience in the area back then who could coordinate boat departures with the tides. There were always tide tables, and then—well, Kurdish luck.

I described the experience in sailing to El-Tor in another post and it sound like that :

““So that you can understand what is written, I need to place you on board a Dabur patrol boat during a long ‘Montana’ cruise.

You’re standing on an aluminum surface that shifts angle, direction, and height in sharp and random movements. It tries with all its might to knock you off your feet and throw you into the sea. You cling to anything you can grab to resist this menace. Sometimes you succeed—let’s see what happens next time. A moment later, the menace returns with a new trick up its sleeve. This time, with a completely different motion from before, it tries to hurl you into the sea even before you lose your footing. This continues again and again, minute after minute, hour after hour.

You’re standing in the closed bridge and looking down to understand what’s soaking your toes. The sealed bridge is leaking from every possible crack and crevice—cracks through which you can see sunlight or ones hidden from view. Green seawater washes over every surface of the ship and finds its way inside, straight to your feet or to the space between the nape of your neck and your shirt collar. From there to the crack of your butt—the path is short. Oof, chills.

Here the Dabur gives you a betzefer (bootcamp-style schooling) and offers you a free lesson in wave theory. Water that passed from one side of the bridge to the other, due to the pitching and rolling, created small waves that collided with other small waves coming from the opposite side. Since the rocking was not at a consistent pace or intensity, amazing natural phenomena were formed—waves canceling each other out or building upon each other. Your toes measure the depth and take part in redirecting the water’s motion. Along the way, new natural phenomena are created. At this point, you are tired. You bow your head and stare intently at the hurried motion of the water. Slowly, you become hypnotized. The motion turns to slow-motion, and the sounds in your ears fade into a single, soft tone.

Boom!!! A mighty crash brings us back to reality. We’ve slammed into a particularly high wave that sneaked up right before the bow of our ship, whose nose, at that moment, was pointed downward as we were still gliding off the previous wave. That sneaky wave struck us head-on and stood like a wall in our path. The boom we heard was the sound of the bow slamming into the wave, merging with another crash—the sound of a red fire extinguisher in the bow compartment that had broken free and, like a cannonball, flew into the wall that stopped its path to freedom.

The strongest among us remain standing upright, soaked with the salty waters of the Red Sea. The less strong lie down, wallowing in their own vomit.

Around us, beyond the roar of the sea, the engines are rumbling, accompanied by the aroma of diesel fumes and black smoke that seeps into every pore of our skin. Some of us are brought to our knees by this damned combination of sea waves, diesel fumes, and smoke.

Escapism in these moments means lifting your gaze to see the stunning beauty of the shores of Sinai and Egypt—a blend of mountains, palm trees, and yellow sands in varying shades, with a deep blue sea splashed with strokes of white from the brush of a drunken painter. Seeing the Egyptian oil drilling and production towers with their torches burning day and night, and looking directly at the white foam trail left behind by the Dabur. To feel in soul and every part of the body what Galileo meant when he was shown the Dabur boat: ‘And yet, it moves!’

Amid all this chaos, I approach the navigation table, and after finding a dry spot on it, I take the notebook from my shirt pocket and write down what I’m feeling in this moment:

‘Sometimes I just want to say, enough!

But maybe “enough” isn’t enough?

Only the roar of the machine

And the splashing foam

Over the raging sea.’“

Entering El-Tor in the early morning was an experience in itself. A katabatic wind blew from the north, down the slopes of the Sinai mountains. In both winter and summer, the wind was bone-chilling. No coat or wool hat helped. Katabatic wind is a local phenomenon, mainly near volcanic islands that rise sharply from the water. Operating under these conditions was difficult. The solution was to approach the pier using radar from within the enclosed bridge, and then quickly dash outside to perform the Docking maneuver and return to the “mother ship.” The maneuver involved dropping a soldier onto the pier, which was covered in wooden planks, where the sand driven by the wind would clean and etch the wood beautifully — like sandblasting. Then the bow was tied with a rope, not too short, not too long. After receiving the OK from the dock, the commander would reverse the starboard engine, advance the port engine, and turn the wheel fully right. The boat strained, and sometimes the throttle had to be adjusted — more reverse or lower RPM — and the stern would slowly inch toward the dock. A rope was thrown from the stern to complete the mooring. Spring lines were added later. The boat was secured.

The Pier at El-Tor

Once tied up, the boat turned into a beehive of activity. Everyone had a role. One refueled from a tanker that arrived from Sharm or sometimes from Abu Rudeis, another dismantled weapons, another filled out the ship’s log. The smell of coffee woke everyone up, and breakfast preparations shifted into high gear. Everyone was a bit wet — some more than a bit. The scent of sweat mixed with diesel and the salty sea, but the smell of toast and omelets overpowered everything. The atmosphere was always good.

After that, we dealt with fixing issues caused by the rough voyage. Some were handled by technicians sent from the base, others solved through crew ingenuity. The bunks were tidied, the boat cleaned and prepped for the next night’s voyage to Abu Zenima. In between — tea or coffee breaks and plenty of chatter. Suddenly, everyone felt fine and shared endless stories from the previous night or back at base. About soldiers thrown from their bunks by terrifying waves, a fire extinguisher gone rogue in the bow quarters, or a bunkmate who vomited into someone else’s shoe.

At night, the boats departed quietly and in complete darkness toward Abu Zenima. We slipped between the coast and a sunken ship, veered far enough from the reefs, and turned right toward a northern course. Sometimes the weather was kind and the sea was extremely calm, almost windless. The still, warm air created unique phenomena worth mentioning.

The radar screen displayed a picture like a map, completely clear on the full 48-mile scale. We made radio contact with distant stations we couldn’t reach before — even without a relay station.

Abu Zenima

One day, while docked in Abu Zenima, we witnessed a Fata Morgana mirage. The sight was stunning and mesmerizing — trees and landscape segments seemed to be uprooted and floated into the sky. Beneath them, it looked like they were rooted in water lakes. These illusions would rise and vanish, constantly changing shape. We had cameras on board, but the phenomenon was so hypnotizing that only afterward did someone ask, “Did anyone take a picture?”

During those days, we could see the Morgan flares far beyond the horizon. Further north, the Abu Rudeis oil field in Balaim was visible. Each of us had a chart marking every drilling tower, but if a new target appeared between them, we wouldn’t have noticed. Our equipment barely met minimum requirements.

Reaching Abu Zenima was easier. The concrete pier there sometimes sat lower than the deck, sometimes higher. We knew there were tide differences but never delved into it — we approached based on what we saw. Now, with electronic charts, I see that the tide differences could reach 4.5 feet — a significant change implying strong currents, especially in this narrowing section between Abu Rudeis and Ras Zaafarana. A northern flow seems like an entrance to a strait. Entry to Abu Zenima was limited to a course less than 110° to avoid shoals to its northwest.

The process of wrapping up and preparing the ship for the next night was the same as in El-Tor. But in Abu Zenima, we felt more like being “in port.” We made a more thorough lunch, sometimes trading food with Bedouins living on the shore. We gave them canned goods in exchange for vegetables or sometimes watermelons — often white inside. Since we didn’t “check with a knife,” we got tricked. There was time to swim in the cold sea, even in summer. We watched Bedouin children who were in the sea every day but didn’t know how to swim. I wish we could get an explanation — one that respects their culture.

Once, with a new crew and no cook, we sat debating how to prepare lunch. I said, without much thought, “We must have soup.” It was hot, and the crew didn’t like the idea. I told them my mom wouldn’t let anyone leave the house without soup, and that it makes you thirsty — which is good in a place where we had to drink one bucket of water a day, not to reach dehydration point. They agreed after I asked for lots of spice. We always had ingredients for soup in the boat store, and it was made — to everyone’s delight. From that day, no lunch without soup.

At night, we patrolled near the Abu Rudeis oil field or north to Abu Zenima. Sometimes we sailed to Ras Sudr, though rarely.

Once, while in Abu Zenima, we were told a high-ranking officer (The “shark”) was coming for a visit. We made coffee and sandwiches as we were about to head out for a night patrol. One of the gunners was uncovering the 0.5 twin machine gun, and since the guns were electrically powered and someone “forgot” to safe the system, a burst fired through the cover, making a flower shape at the tip. Right then, the officer arrived and asked if he’d been “targeted.” We all laughed, drank coffee, and carried on.

On the way back, we patrolled near El-Tor, stopping there for a day’s rest.

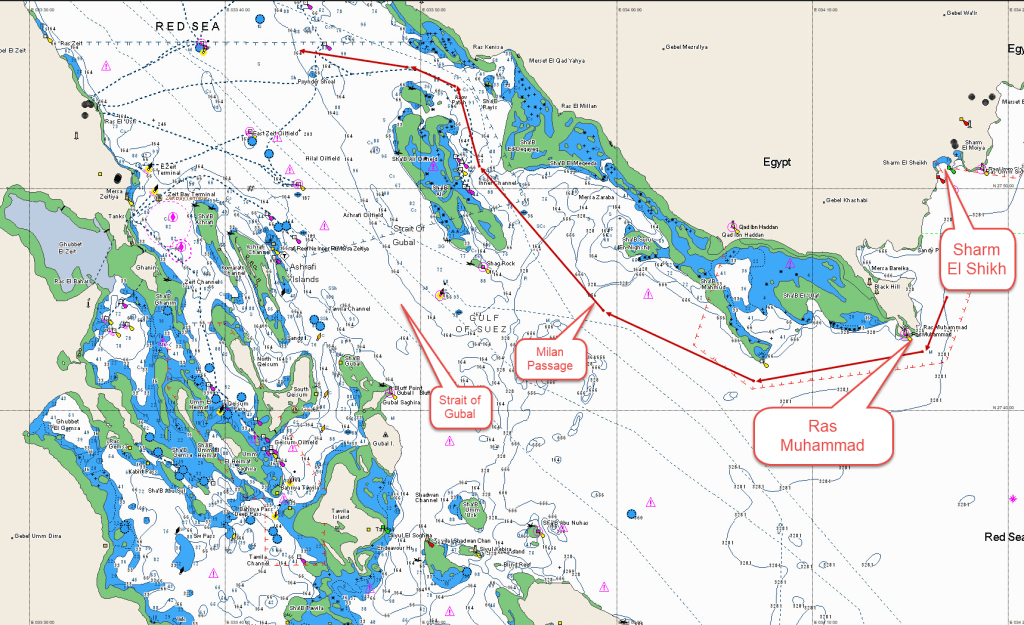

Usually, we returned via the Jubal strait, but sometimes we passed through the dangerous Milan Passage.

Map of the Milan passage

Before I arrived in the area, the Navy had placed a radar reflector on one of the reefs in the middle of the Milan Passage. It was barely visible, supposedly to keep the passage secret — known only to us. We navigated the passage using landmarks on the Egyptian coast: Balaf Point, Ashrafi, and Shedwan. The radar reflector was only used for range checks during the crossing. We were nervous about navigating it — until Ami Ayalon arrived. He immediately understood its importance, and we began practicing the passage on almost every patrol. I remember my first voyage with Ayalon through Milan. I navigated from the chart table while he stood by the helmsman watching the depth gauge. As we approached a reef — a small underwater hill clearly marked on the chart — the depth dropped from 12 fathoms to 9 for a moment, then back to 12. I told him that would happen — and it did, exactly. Ayalon saw that accurate navigation was possible, even more precise than with our older boats, and thus Milan was adopted.

During wartime, everyone realized the importance of the Milan Passage.

Another thing Ayalon tried that voyage — standing on the open bridge with a snorkel mask to serve as a “lookout.” The open-bridge lookout was a sore point in local patrols. Standing orders required a lookout on the open bridge at all times. These rules applied to all seafaring vessels. But in our region, where the sea was usually rough, it was impossible. Sprays drenched your face so fast you couldn’t wipe it off. After a few minutes, your face and eyes stung, and you couldn’t see a thing. Early in my service, I tried wearing a suit given to me by a friend from the Dimona nuclear facility. It was made of thin plastic and kept my body dry — but not my face. In daylight, it acted like a greenhouse. Heat came in and couldn’t escape. Within an hour I was soaked in sweat — maybe more than the seawater would’ve done. The suit went straight to the trash. Maybe it protects from radiation — but not Sharm’s sun.

So, Ayalon stood there on the bridge, with a snorkel and mask. Funny? Very funny. He realized it didn’t work because of the fogging. The lookout issue remained unresolved.

Leave a comment