In 2014, Menahem Raznik (Class 20) and I planned a sail to Nantucket straight from the winter marina in Haverstraw, New York, where the boat stands on its keel, out of the water, waiting for summer to be launched.

We set out early Friday morning from the Hudson marina heading South toward Staten Island. Haverstraw is a small town about 35 miles north of the Hudson’s mouth. The town has a marina in a natural bay that was deepened for the construction of the original Tappan Zee Bridge. The concrete caissons, which looked like giant boxes, were floated downriver and sunk precisely into place to serve as the base for the bridge’s foundations. This was the boat’s first sail of the season, and although I’d prepared thoroughly, I worried that I might have forgotten some small detail—something that would “bite us later.”

The boat functioned flawlessly, although I discovered I had forgotten my toiletries and the foul weather gear I’d taken home to wash at the end of the previous season. I did have two lightweight storm jackets on the boat, so it wasn’t a big issue.

New York from the Hudson river

Statue of Liberty

Sailing south down the Hudson was as enjoyable as always, though we had to motor since there wasn’t enough wind. The Hudson changes its current direction every six hours, so we timed our departure toward the end of the northward flow—when it’s weakest—in order to maximize the southbound current. It’s important to understand that the tide moves from south to north, so when sailing southward, the window of favorable current is shortened. It’s similar to flying west to east—the flight time during daylight is shorter than the actual hours of daylight along the route.

The Hudson flows along the path of a prehistoric glacier and passes near the Palisades cliffs in New Jersey, offering breathtaking views that blend beautifully with Manhattan’s concrete and glass skyline. We passed under three bridges—Tappan Zee, George Washington, and Verrazzano—and even paused to admire Ellis Island and the Statue of Liberty.

At Staten Island, we tied up to a friend’s mooring ball—he hadn’t yet moved his boat from winter storage. It was a bit complicated because the mooring line wasn’t prepared. Staten Island’s marina is also in a natural bay, surrounded by beaches and reefs, with access through a narrow and winding channel that’s dredged every few years.

We had to approach the mooring stern-first to thread a line through the shackle. I pulled a line from the starboard locker but forgot to close the hatch. Menahem was at the helm, focused on the mooring, and didn’t notice the open hatch. When he stood up for a better view, his foot slipped into the locker, and he banged his leg. I quickly grabbed a bag of ice cubes from the fridge (originally meant for our drinks) to treat the swelling, which was already changing color. I completed the maneuver, and we secured to the mooring.

I felt bad—it reminded me of a scatterbrained friend from my missile boat days who often had similar mishaps. Menahem was in pain, but the ice helped. We toasted the day with a Dark ‘N’ Stormy.

The smartphone apps I had installed disappointed me on the way down, especially the GPS-related ones, which didn’t work properly. At the marina, I decided to investigate. Turned out the GPS on my phone wasn’t functioning. The fix, as always, was a reboot—once restarted, everything worked flawlessly.

Menahem cooked a lovely dinner with much skill and good spirit. We reviewed the next day’s sailing plan and turned in for the night.

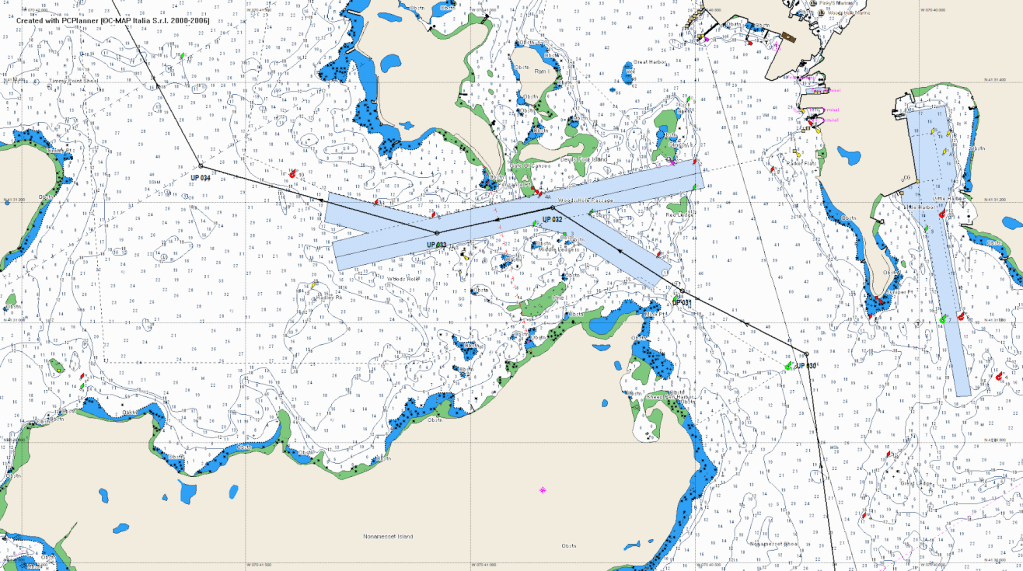

2nd day track

By 6 a.m. on Saturday, we were underway again. We departed with the fishermen, eager to take advantage of the morning’s cold waters. With no wind, we motored through the channel to Ambrose Channel, the main entry to New York Harbor. At its southern tip once stood a lighthouse welcoming ship to New York.

From a point southeast of Brooklyn, we headed northeast along the coast, maintaining a distance of at least three miles offshore to avoid scattered fish farms. By late morning, after a fine breakfast, a light wind picked up—enough to raise the asymmetrical spinnaker I have on board. Though sailing with a spinnaker can be tricky, I knew that with Menahem, we’d manage and it was a good chance to gain experience.

I rigged the lines, checked the halyards, and prepared the setup. Menahem was at the helm and hoisted the sail bag to the top of the mast. I pulled the line, and the colorful sail unfurled smoothly. After a few minutes of adjusting, we hit an optimal sailing state. I turned off the engine, and we continued for 40 exhilarating miles under spinnaker along the southern coast of Long Island, which from the sea is rather dull. Occasionally, the wind picked up, and we considered dousing the spinnaker (our rule: no sailing with it in apparent wind over 20 knots). Toward evening, the wind died and shifted counterclockwise about 20 degrees—continuing on that sail would have pushed us ashore.

We lowered the spinnaker easily and continued under power, with the sunset behind us.

At night we took four-hour watches. During my Morning watch, I noticed we were entering dense fog, typical for this area in the season. At first light, we were near Montauk, the eastern tip of Long Island. Even three miles from shore, we couldn’t see it.

We kept going through strong currents between Long Island and Block Island. Using the autopilot, set to a waypoint on the chartplotter, we noticed a significant offset between the boat’s heading and actual track—up to 40 degrees—due to the current. For instance, our bow pointed toward Block Island’s center, but we were sailing to a point 2.5 miles south of it. Before chartplotters and autopilots, such navigation required lots of experience and intuition.

Menahem joined me in the cockpit for vigilant watch, especially for reckless powerboat fishermen who acted as if there was no fog. We exited the fog near the Elizabeth Islands and Gay Head cliffs at the western tip of Martha’s Vineyard.

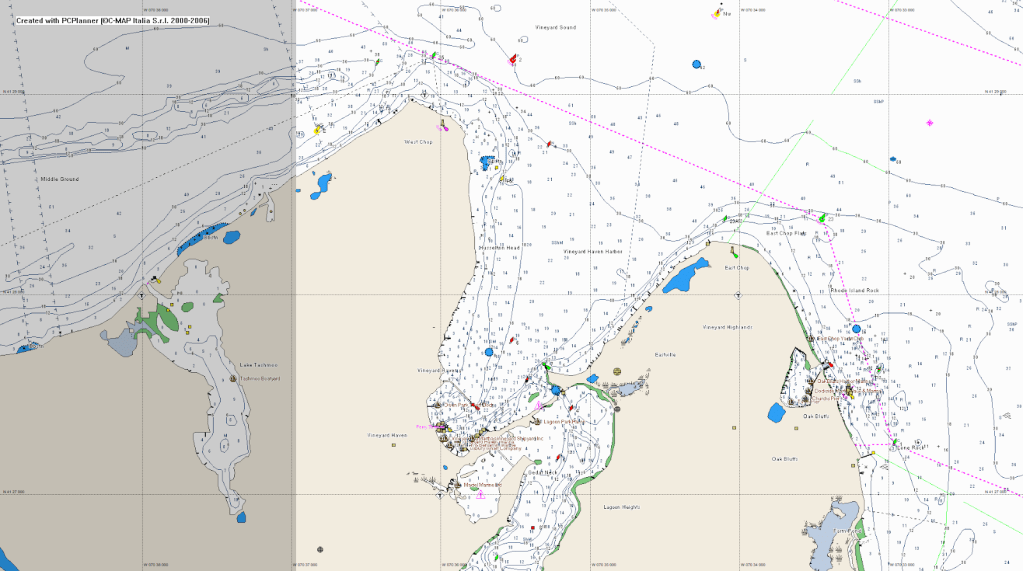

We sailed into Vineyard Sound, where the fog lifted, and entered Vineyard Haven, the island’s main harbor, tying to a mooring at 3 p.m.

Vineyard Haven

We learned a lot—sailing through fog and currents, and were surprised by how far offshore we now had cell reception (3G was new then). Via phone, I learned our friends wouldn’t be joining us—their engine had failed because they hadn’t changed their water pump impeller in five years, despite my warnings.

We took the launch ashore, scouted the harbor for the next day, ate terrible pizza, and returned to the boat to sleep.

In the morning, we went to the fuel dock, and of course, the fuel attendant didn’t show up on time.

We tied up anyway to a dock not designed for boats like ours, placed fenders between the boat and the pilings, and I looked for a water hose to fill the water tanks. During the voyage yesterday, I realized that during the preparations—while cleaning the tanks with disinfectant and rinsing them thoroughly with fresh water—I had forgotten to fill one of the tanks completely, and it ran out early on the second day.

While refilling the water, the maintenance guy at the dock decided to shut off the water to replace the faucets on the pier. The fuel guy finally showed up, and while refueling the boat, I had to help the water guy with some plumbing work, and together we installed the new faucets.

Once we finished fueling and filling the water, we returned to a mooring closer to the breakwater of the harbor.

Vineyard Haven.

We went ashore and rented bikes for a ten-mile ride to Edgartown, a picturesque town east of Vineyard Haven. We pedaled along the coast through a charming town called Oak Bluffs, where we stopped for a light breakfast, and continued along the coast to Edgartown.

The place is stunning, although very touristy. We ate at a seafood restaurant and returned via the main road that cuts through the center of the island. There’s a dedicated bike path along the road, and motorized bikes are not allowed on it.

The ride back was pretty hard for me. I’m not fit enough to ride 30 km in one day. Menachem comforted me and said it was tough because my bike wasn’t in great condition.

Bicycles in oak bluff

Back on the boat, we made a plan to sail to Nantucket the next morning. We took a good shower and went to sleep.

The sailing plan was made in advance to take advantage of the currents in the area, and the forecast predicted favorable winds that matched the direction of the current. Everything looked promising.

Nantucket is the island from which the whaling ships used to depart in the past (like in Moby Dick).

We woke up at six in the morning (Tuesday) and started preparing the boat for departure.

The wind blew as forecasted, and we had to reach a point north of the anchorage by 8:30 a.m. to start the passage to the island with favorable currents. All good.

Menachem suggested we listen to the Coast Guard weather forecast, and so we did.

Total surprise.

A tropical system near Florida was expected to develop into a tropical storm or even a hurricane, heading northeast—right toward us.

We realized there had been a drastic change in the forecast and that it required a drastic change in our plans.

History teaches that disasters happen when people ignore weather changes due to pressure to stick to a schedule or commitments.

For us, it wasn’t a big problem to change plans.

The sail east to Nantucket had been planned with the wind and current, but sailing back west would mean going against both.

So we immediately set sail west to catch the edge of the westbound current. But the west wind blowing against the current made the sea choppy and the sailing slow and unpleasant.

At some point, the current changed, and even though we were going against both wind and current, the speed didn’t drop much and the sea became a bit more comfortable.

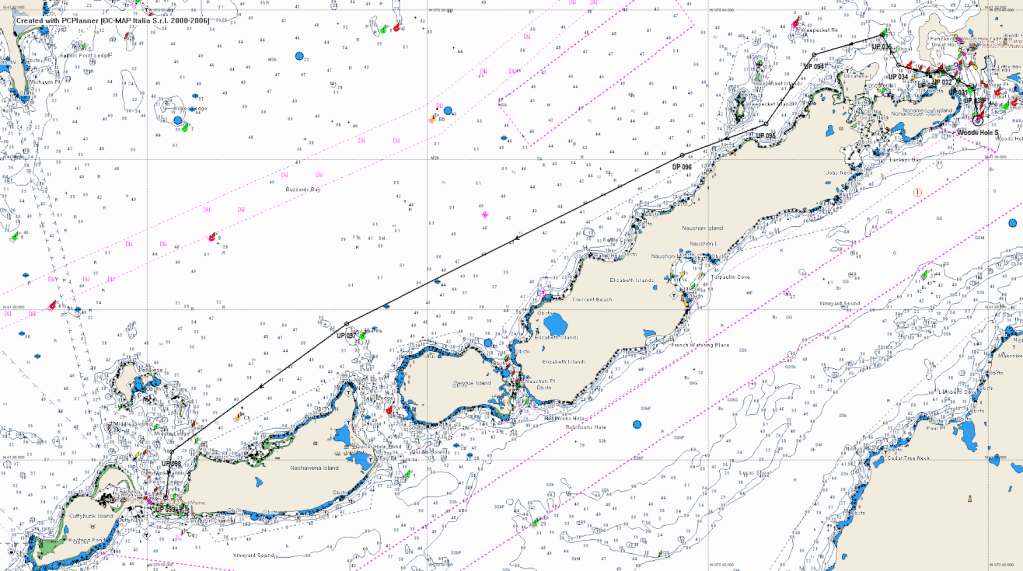

We decided to sail to Cuttyhunk, the westernmost island in the Elizabeth Islands chain. The anchorage is in the north side of the island.

As we approached the Woods Hole passage, we had to decide whether to continue around the Elizabeth Islands from the south or go through the passage between two islands and then continue north of the islands, in a route sheltered from the southwest wind.

Woods Hole Passage

The strait between the islands is tricky to navigate, even with the current in your favor, and extremely dangerous if it’s against you.

Our savior was the Navionics app, which proved to be indispensable. No need for tide tables or stories. It gave us real-time current data that helped us make precise navigation decisions wherever we were.

The app showed that if we passed through the strait, we’d be going against the current.

I spoke with Menachem about the situation, and we decided to try passing the strait even though the current was at its peak for the day—about 3.5 knots.

The wind wasn’t against the current, which encouraged us to try.

American-born sailors would never attempt such a move, but we come from a place where challenge dwarfs fear, so we went for it.

How do you do that?

You plot waypoints on the chart plotter at the turning points. You click on the plotter to “Go To Waypoint,” and it draws a dotted line from the current boat position to the waypoint.

You engage the autopilot with the tracking button. The plotter beeps for you to make sure there’s no obstacle in the bow’s direction. All clear? One more click to engage, and the battle begins.

The forces of nature (current and wind) versus electronics, backed by 50 HP.

The boat had a slight advantage over the current (about 1 to 1.5 knots).

Even though our speed over ground was low, the water moving past the rudder was strong, so we had good steerage.

The autopilot navigated us to the next waypoint, and we only had to make sure we were staying on the dotted line.

Anyone with a weak heart shouldn’t stress about the direction of the bow—it only makes sense if you understand vectors.

We were ready to switch to manual steering if we drifted off course and turn back, defeated.

Fortunately, the engine and electronics won the battle and did the job.

At the end of the strait, we breathed a sigh of relief.

Sailing north of the Elizabeth Islands

We continued on a pleasant sail to the beautiful island.

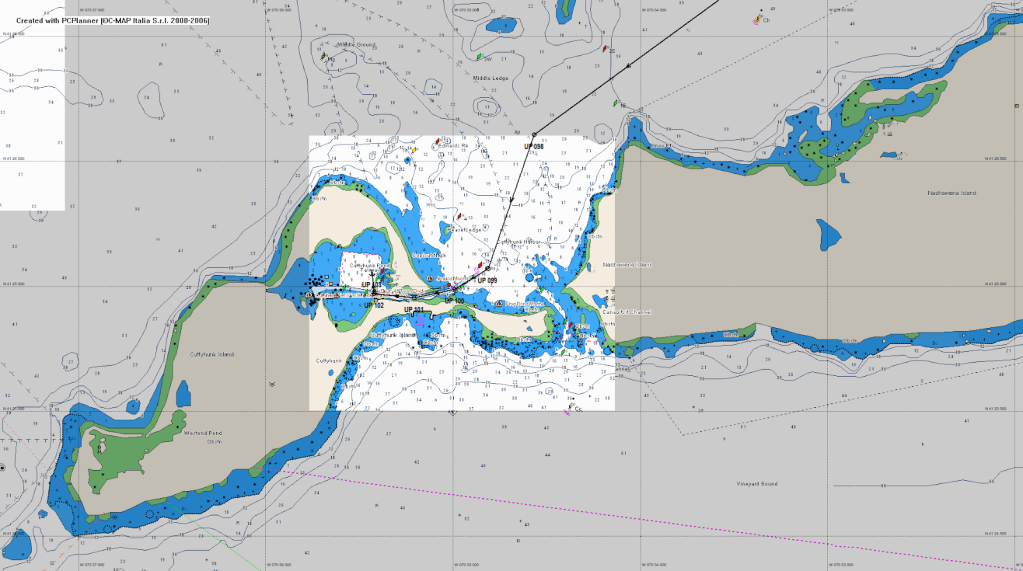

We entered Cuttyhunk, a natural bay via a channel in the early afternoon.

To my surprise, the anchorage was only half full. It was right before the Fourth of July, when anchorages are usually packed the week before and after.

Apparently, most sailors were aware of the weather changes.

Cuttyhunk

We went ashore in our dinghy. The engine started immediately and without issues.

We took a short tour of the island. It’s small and picturesque. Cars aren’t allowed—only electric golf carts.

At the center is a hill that offers views of Martha’s Vineyard and the surroundings.

During WWII, it served as a military lookout.

The island isn’t touristy, aside from the crews of boats moored in the anchorage.

On our way back, we tried shrimp cocktail made from fresh, locally caught shrimp. You can’t compare it to supermarket shrimp.

We picked up the swordfish we had bought earlier for dinner (also locally raised), and Menachem cooked it masterfully on the boat.

The fish was fresh, melted in our mouths, and left us wanting to return to this magical place.

Every day, especially in the evenings before bed, we’d sit in the cockpit, and conversation would flow freely.

It usually started with the Yom Kippur War—sharing unknown details, talking about Marsa Talmatt (it always comes up in different flavors), and other chapters from our military service.

Menachem and I met in Sharm before the war, went through it together, and parted ways a few months later.

We met again by chance at Ami Sharel’s daughter’s wedding.

The conversation picked up exactly where it had left off 33 years earlier.

We’ve been in close contact ever since.

The next day (Wednesday), again at six a.m., we set off for Newport.

When we left Buzzards Bay, a fresh southern wind picked up and we fully enjoyed a sail-powered trip toward Newport.

We arrived in the area around 1 p.m. and debated whether we should continue to Stonington to be within a long day’s sail of Stamford Marina, so we could return early.

We didn’t want to spend two rainy days (forecasted from the nearby hurricane) in a random harbor.

To continue, we needed to check the current in the Watch Hill Passage.

Navionics again came to the rescue. If we reached it before 3:30 p.m., we’d still have favorable currents.

We changed course to pass south of Point Judith, just south of Newport.

The course was close to the wind direction, so we used the engine to help the boat head into the wind.

From there, we turned right, off wind, and continued directly to Watch Hill under sail alone.

Passing the strait by sail was a first for me (it’s not usually done in narrow waters).

We reached the Stonington marina at 3:30 p.m., and again had no problem finding a mooring ball—most sailors had skipped the holiday on the water.

From Watch Hill passage to Stonington

Stonington, CT

Stonington is a charming town that once housed the captains of whaling ships.

We walked the entire main street to the water, where there’s a lookout over Fishers Island.

On our way back, we heard a siren moving with us from house to house. It was strange and needed investigation.

There were no signs of fire or anything suspicious.

Eventually, I checked my pocket and found out that the anchor alarm on my smartphone had been triggered—in my pocket.

Too much electronics!

In the evening, we enjoyed the private showers at the marina and had dinner at “Dog Watch Caffe” the marina restaurant, which I think is the best in the area.

The marina was extremely helpful and made us feel that our money had been well spent.

They even loaned us a car for a provisioning run in Mystic.

The next morning (Thursday), at 6 a.m., we headed west toward Stamford.

It was a long sail—70 miles—but doable this time of year when the days are long.

We sailed into dense fog, requiring us to use radar almost constantly.

Menachem and I stood in the cockpit, alert to every movement around us.

Until then, I hadn’t used the radar seriously—only tested it. The image wasn’t amazing, certainly not like what we were used to from naval systems, but it was very helpful in spotting moving targets and navigation buoys scattered throughout the bay between Fishers Island and Connecticut.

Once we exited the bay, visibility improved to nearly normal.

We motored, switching to sails when the wind picked up.

We crossed almost the entire Long Island Sound, the long bay between Long Island and Connecticut.

We tied up at the dock in Stamford in the late afternoon.

Five minutes later, it started pouring.

The boat was cleaned Friday morning, just before the full hurricane rains arrived, and we headed home happy and satisfied.

On Sunday, after the hurricane rains stopped, we sailed to Port Jefferson.

We tied to an abandoned mooring ball.

Our friends from the marina, whose boat had since been repaired, were with us, and we explored the area together.

The anchorage is far from town, so it’s very quiet and picturesque.

We ate meals that Menachem cooked on my boat and returned to the Stamford marina on Tuesday.

In summary:

We really enjoyed the voyage. There were interesting events that required us to think and respond, and I believe we made good decisions that kept us away from uncomfortable situations.

Menachem managed the boat skillfully throughout and handled the kitchen like never before.

I thoroughly enjoyed sailing together.

And, as usual, the boat did not disappoint.

My friend Menachem

Me

Leave a comment