1972.

The voyage through the stormy Straits of Tiran was sometimes difficult due to the high waves in the strait. Over time, I learned that we had not been aware of a natural phenomenon well known in other parts of the world — the phenomenon of current versus waves. In the northeastern United States (and on other coasts), most of the shoreline is affected by tides. The currents caused by the tides are active 24 hours a day and change direction approximately every six hours. Wind, however, is determined by air pressure and thus has no correlation with the tidal currents. When the current is strong and the wind blows against it — even if the wind is mild — you see whitecaps. These wouldn’t normally appear on the Beaufort scale with such light wind. But when a strong current opposes a strong wind, standing waves form — tall and close together, they look from the vessel like walls advancing toward it. When wind and current are in the same direction, the waves are not affected.

This phenomenon is more pronounced in straits (like Tiran) where the current intensifies. The same effect occurs when a land breeze opposes a relatively weak current, such as in the El Qura area.

The boat sails in a relatively narrow gulf, flanked by mountains and desert — a landscape shaped by God, untouched by man. As we approached Eilat, the waves subsided, and the entire crew gathered on the open bridge to welcome the city. We tided the boat to the concrete pier to prepare for the dry docking. We offloaded fuel and ammunition and transferred everything to the ammunition storage. The base was mostly dormant, without vegetation, appearing neglected, and spread on both sides of the road leading south to Sharm el-Sheikh. The separation required two guard posts, which was a heavy burden on the base. The guards, out of sheer boredom, would sometimes play “quick draw” games that occasionally ended in accidental discharges. According to legend, at one point the guards were even given bows and arrows for base security.

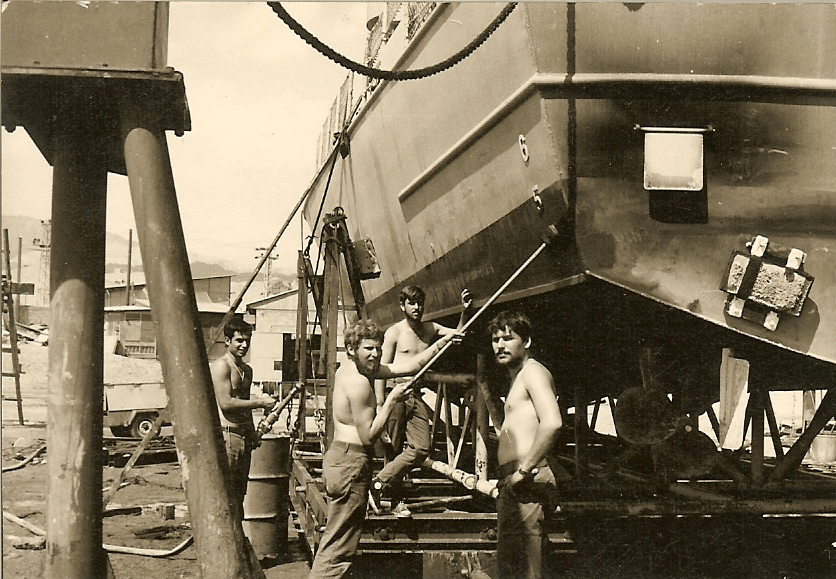

The next day, we aligned the boat with the “cradle cart” and pushed it onto the cart that moved on rails into the water. We tied the boat to poles sticking out of the water around the cart. The winch onshore then pulled the cart, with the boat on it, back to land. Then began the work of scraping off the marine growth and cleaning the hull — a task for the ship’s crew, including the commander. Later, the shipyard workers took over, and we were released into the arms of the base and the wonders of the city of Eilat.

Once, I had to bring a boat with a malfunctioning engine onto the cradle. The harbor was protected by a fence that extended to the seabed and gates that were opened by a tugboat to allow vessels to pass — all to protect the vessels from underwater sabotage like the sinking of the INS Bat Galim in Eilat harbor. I left the pier heading toward the harbor gate. The sluggish tug only opened one section of the three-part gate. Confident in my skills, I proceeded, with only one engine running, into the narrow opening against the northern wind. I managed to pass through, but I felt a slight scrape against the gate post.

We got the boat onto the cradle, and I rushed down to check for damage. My eyes darkened. On the left hull side, not far from the stern, the gate post had cut the aluminum hull like a knife — a clean slice, “durch and durch.” I was very upset with myself and called the arena commander office. I reported to “Shark” what had happened and asked to be relieved of command of the Dabur — because I was only wrecking them. “Shark” told me to calm down and said, “Only to Rabbi of Zikchron things like this never happen.”

I returned to the boat and spoke with the shipyard workers, who promised the repair would be simple and easy. A few cans of Sardines, and the fix wouldn’t even be documented. The boat was repaired before the engine fix was complete, and everyone was happy.

In the living quarters, most air conditioners were “desert coolers”, which work by pushing air through a wet medium. This added a lot of humidity to the room. The cooling worked well only when the pads were clean.

The dining hall served “regular” food, but what I especially remember fondly is the Sour cream served at breakfast. It was a delicacy that motivated us to wake up for breakfast after a night out in Eilat.

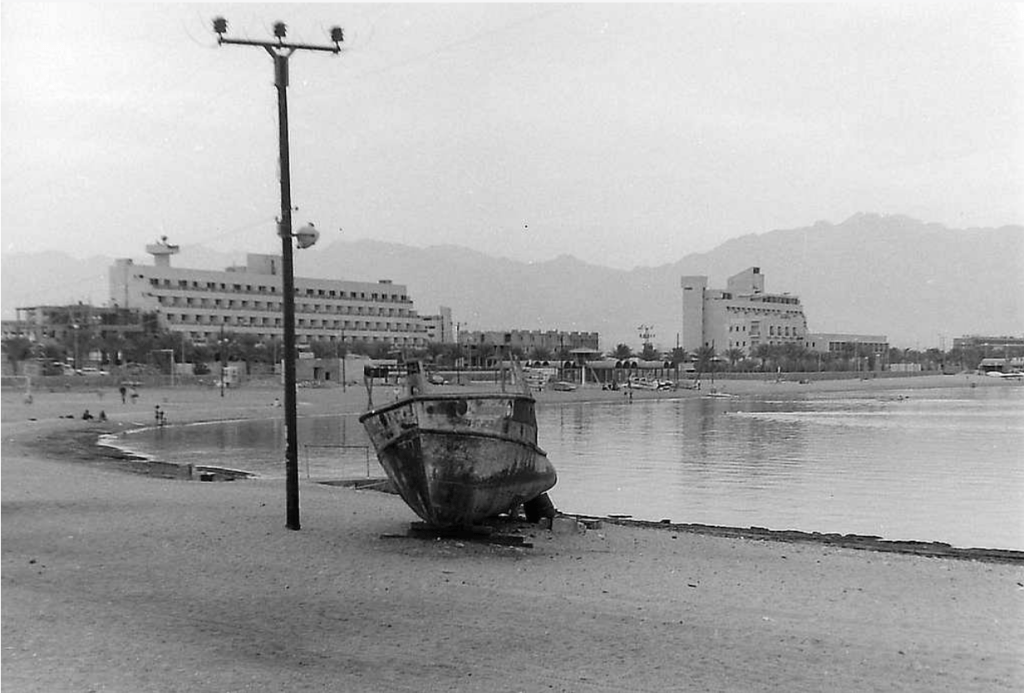

The city of Eilat was a refuge. It had one cinema in the town center, a few good restaurants, and a number of hotels you could count on one hand. At night it looked “pale” compared to the lights of Aqaba across the border.

I remember a performance I saw at the cinema.

I met Lieutenant Ora Abramov, the female commanding officer from Sharm, a wonderful girl from Moshav Merhavia, descendant of the founding generation (daughter of Zalman Abramov, one of the founders of the naval commando). We went to the Eilat cinema to watch a show titled The Good, the Bad, and the Girl, which was popular at the time. The show was supposed to start at 9 p.m., but of course, it didn’t begin on time. The locals reassured us, saying that in Eilat it was “customary” for things to start late — but a promise is a promise, and the show would happen.

At midnight, Benny Amdursky, Josie Katz, and Israel Gurion went on stage and gave the performance of a lifetime. They sang the beautiful songs of Shmulik Kraus. The audience received them warmly and didn’t hold the delay against them. We returned to the base in the middle of the night. The gate guard was dozing on duty. The performance was very special because it embodied the laid-back vibe that everyone was trying to project in those days. It fit well with the appearance of the bases in Eilat and Sharm.

On one of the outings, I went with Lieutenant Zehavi, a maintenance officer from Sharm. He was a quiet guy but had a mysterious aura of someone who had acquired a lot of “knowledge” in the field of women. I hoped some of that aura would rub off on me, so we headed into town.

We started at the local snooker club.

We began playing on tables larger than the ones in the officers’ club, and the balls were smaller.

While we were playing, a large-framed man with long curly gray-streaked hair entered. He walked over to our table and stood watching. It was my turn to strike, and he said, “Gingi, you’re not making that shot.” I replied, “Gingi makes that shot.”

I hit the ball — and in it went.

“Ooh,” he said, “maybe just luck?”

“Now, Gingi, no way you’re making this shot.”

And I answered, “Gingi makes this one too, no problem.”

I took the shot — and the ball went in.

At that point, Zehavi pulled me aside, politely apologized, and whispered in my ear, “That man is Busi — did you really pick him to mess with?”

After that, I stopped being cocky and switched to polite mode. My hand shook, and the balls missed.

For those who don’t remember, Bustanai Sacha, nicknamed “Busi,” was one of the major crime figures in the country. He was born in Sha’araim, where he began his criminal career. In adulthood, he even lived in Bat Galim, not far from the naval base, and legend has it that one day his partner, Naomi Adva, was seen running naked through the streets of Bat Galim with Busi chasing after her. He was eventually forced to settle in Eilat and banned from going north. During the naval officer course, there was a cadet in my class from Nahariya named Ze’ev Kober who used to dream at night of “how Busi would be murdered in the street in Eilat” — and indeed, a few years later, Busi was murdered in the middle of a street in Eilat.

From there we headed to the north side of town to eat at a special restaurant on a street called “End of the World.”

I vividly remember a surreal sight — long, simple tables made of plywood, benches along both sides, string lights above, all outdoors under the open sky. The furniture was set on sun-hardened dirt clumps, with the sunset falling between the mountains beyond the “end of the world.”

Soldiers and officers sat on the benches, dining from plates piled high with “white” meat (pork) steaks. The portions were excessive, and the restaurant owner stood nearby, urging us to finish our food, because we were soldiers — and we had to be strong.

From there, with full bellies, we returned to the base. I went to bed, and Zehavi went to another “knowledge-expanding” meeting in his field of expertise.

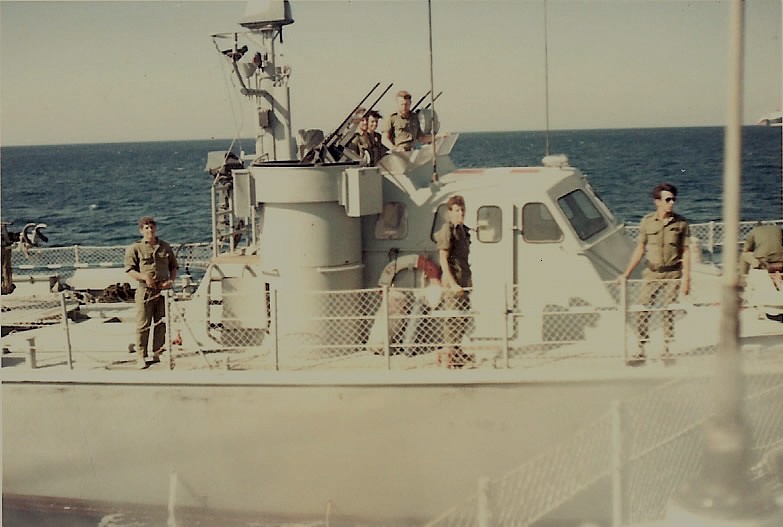

Near Eilat. Picture taken from another boat.

Hard at work

Eilat Beach at 1972

Leave a comment