One of our favorite holidays in childhood was Lag Baomer. The tongues of flame scared us all, but challenged our young minds to prove we could overcome and master that fear.

It began with searching for a suitable spot for the bonfire, which usually ended up on the field across from our home. Two houses across from ours stood back from the road. Many years later we discovered that this empty lot had originally been planned for a small colony garden. The original neighbors had grown used to— and didn’t oppose— our use of the space. However, when they moved away, the new neighbor, the “Koshitza,” did not consent to our regular bonfire location. With no other option, we moved the fire to the strip between the road and our fence. The spot was poor in every respect. Still, we lit a fire beneath power lines and close to our Hedgerow fence which could have caught flame and caused a much bigger fire than intended. On top of all that trouble came another in the form of Sabbath desecration. We kindled the fire on Saturday night after Shabbat. We all stood around, looking skyward for three stars so we could sanctify the holiday’s mitzvah. Our effort was in vain, and we were scolded by a religious neighbor, who pointed out that we had desecrated the Sabbath by working on it to build the fire. He said the mitzvah of observing Sabbath takes precedence over the mitzvah of a bonfire in Lag Baomer.

I got a bit carried away with the story and forgot to describe the backdrop and preparations for that fateful moment when the bonfire lighting ritual took place.

Bonfires blazed throughout the moshava (colony). Many were neighborhood gatherings, and even more were sub-neighborhoods— that is, a number of children who lived in one block, plus close friends from other blocks. Team assembly was carried out in great secrecy. On Independence Day eve, according to tradition, we celebrated with a late-night campfire sing-along after the dancing at the central station. It was at that sing-along that the team and the plan were formed.

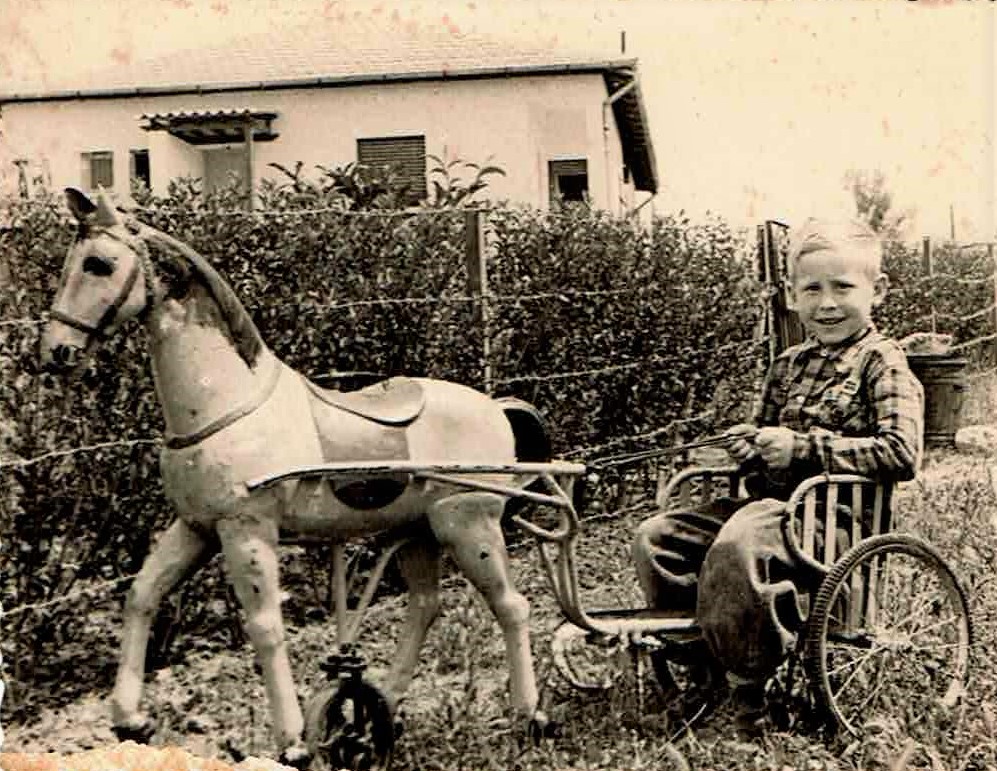

Preparations began with a meeting of friends and a trip to the “industrial zone” to search for and collect planks— mostly broken crate boards from the “Hadofek” carpentry shop, which repaired oranges and fruit crates. We also gathered planks and other combustible material from other carpenters’ workshops. We loaded up the cart that Zavi and I had built from a crate with a plank underneath it, in the middle. On it, we attached wheels from baby carriage wheels, with a perpendicular plank at the front affixed to a shaft tied by ropes at the ends so we could steer the cart left and right. There was even a brake. When we pulled the top end of a rod connected by a large nail or a rusty screw to the crate, the bottom end pulled on a wooden board connected by two strips of old leather shoes tongue to the back of the crate. This board pressed against the rear wheels and acted as the brake. The journey from the industrial zone to our material storage site was heartwarming, and we never missed an opportunity to participate. Besides the wood, we sometimes found metals like aluminum, zinc, and copper, which we took to sell to a frugal yet friendly fellow named Zakuto, who lived in the “temporary housing.” That’s how we built a budget for supplies that sweetened our Lag Baomer feast.

We also roamed the fields and groves near our home, just beyond the row of houses opposite ours. In the groves, we found dry trees and dry branches that the orchard workers had pruned. We could carry off the branches, but moving the trees required ropes tied to the trunks and a group pull. The tree budged slightly, but sometimes we realized it was an impossible task. I told my late mother about the difficulty hauling the tree, and she came and tugged the entire tree out by the trunk— all by herself. Yes, alone. We followed her in astonished silence.

As the special day approached, a pile of wood and planks already stood in front of the house. The pile created a new problem. We feared children from other neighborhoods would come and take what we had prepared or, God forbid, set our stack ablaze as a prank days before Lag Baomer (rumors like that circulated in the moshava). Sometimes we posted guards during the day, and at night I’d creep to the window several times to peek through the shutter slits at the pile.

As the date drew nearer, we began planning the offerings. Baked potatoes were a pre-agreed item since Lag Baomer without “kartoshkes” (potatoes) isn’t Lag Baomer. The preparation was simple. We threaded a piece of iron wire that we’d found in the industrial zone through the potatoes and twisted the two ends of the wire together. We tossed the ring of potatoes into the dying coals after the main bonfire had burned down. The wire loop was so we wouldn’t lose a single potato and so it was easier to pull them from the embers. The iron wire was usually rusty, but we didn’t bother with such trivial issues then. I’ll describe the other offerings later.

On the morning of the bonfire lighting, we gathered— the friends— under the power pole to carry out an important part of the plan. A streetlamp was mounted on that pole, shining brighter than the mercy of heaven on our fire. We weren’t willing to compete with such illumination, so we needed to smash the lamp. Throwing stones by hand is good exercise but doesn’t break glass. We fashioned a “miklōa” (slingshot) from a branch of our hedgerow fence, one that split in two. We cut rubber bands from inner tubes and used an old shoe’s tongue as the pouch for the specially chosen stone. After many attempts, we heard the “pit-z” that told us the mission was accomplished.

The bonfire lighting process itself demanded hours of planning and preparation.

Without bows and arrows, it’s not Lag Baomer. We tried to connect the two— the bonfire and the bow. The idea of igniting the fire with a flaming arrow shot from the bow thrilled our spirits, and we’d only seen it in the daily shows at the Nave Cinema. In movies about Romans and Indians, it always worked, but in our case it mostly failed. The flame on the arrowhead was extinguished by the speed as the arrow left the bow. When we soaked the rag at the arrow’s tip in more kerosene, it sprayed fire that threatened to burn the archer. After many attempts, we abandoned the idea and settled for hurling a burning torch to the center of the woodpile— to the area we’d first doused with kerosene taken earlier from our home’s kerosene tank.

One year, when we were already teenagers, we brought the kerosene in a canteen to the bonfire we’d set in the “dry field,” a field that connected the houses of Ness Ziona and the cactuses fence of Kibbutz Netzer Sirani. Emmanuel Shpilman, our friend who always tried to impress, was thirsty and drank greedily from the canteen without touching its spout to his lips. Like in the movies. That event passed without medical treatment. We, as children, were “vaccinated” against such trifles.

Next to the bonfire, we dug a small pit for preparing food and drinks to accompany the potatoes. We placed glowing coals from the main fire in the pit. Over the pit, we set up an iron grate— usually used to scrape mud from shoes— and placed a large tin can on it that had formerly held pickles. The can came from the neighborhood shop owned by two Holocaust-survivor brothers we called Dzigan and Shumacher. In the tin can, we brewed coffee to go with the potatoes and the “lipiyushkes” we made at the same time. “Lipiyushkes” were pita breads we baked in a pan beside the coffee can, from flour, water, and a bit of oil— also an initiative of my late mother, who smartly compensated for what was missing given our limited means. In those days, there were no pita breads in the moshava shops.

By the bonfire, we sang and danced a little, but mostly we stood with our eyes wide, watching the tongues of flame rise. They took shape and morphed, their color changing from one moment to the next. Sparks flew all around us, and we tried not to stand in their path, moving toward and away from the fire in a continuous dance that wasn’t preordained.

At the end of the evening, after we finished eating, had our coffee, and only a layer of glowing embers remained on the ground, we kept the girls at a distance and the boys would urinate on the remains of the fire (we called this “scout extinguishing”), all amid cheers and rejoicing. A two-way hose from the faucet by the gate whispered the final extinguishing of the embers, thus ending a true celebration. Until next year.

“Those were the days, my friend

We thought they’d never end”

Leave a comment