Sometime in 1981, I was called up for reserve duty to command a Dabur patrol boat at the Ashdod base. Reserve service at that time was fun for me. I had already finished my studies. A few sails as a break from work and wife, in the company of a younger crowd with all that implied, sharpened my curiosity and added some excitement.

I walked around the base without rank insignia to avoid making the commanders—who were of lower rank—feel uncomfortable. I knew the crew knew I was the commander, and that was all that mattered.

We went out on patrols near Tel Ridhan or far offshore. The deep-sea patrols were quieter because they were out of radar range from shore. Even though we knew our location with “above approximately” accuracy, no one nagged us. We reported our position to the best of our knowledge.

The patrols near Tel Ridhan were more interesting due to the constant friction with Gaza fishermen who tried to fish even near the KATZA (The Eilat-Ashkelon Pipeline) oil buoys in Ashkelon.

During one of the deep-sea patrols, a serious southwest storm developed unexpectedly, which hadn’t been in the forecast, and life started getting tough for the seasick crew members.

I heard over the radio that patrols up north were being called off and the boats were returning to safe harbors. Our vessel was already being tossed by the quickly developing storm.

I had two options:

- Return to Ashdod port and enter at night through the heavy breaking waves and strong wind, risking the crew and the vessel.

- Stay at sea and alter our patrol course and speed from what the mission order dictated. Wait for daylight and maybe an improvement in the weather. In Sharm El Sheikh, heading north via the Yuval passage, such a sail would have been routine—even in such rough seas or worse.

I assessed the storm as local, not a meteorological system, since it hadn’t been forecast. I had the advantage of being far from shore. Even a full night of sailing stern-to-waves with the engine on just Forword wouldn’t beach me. I tested a few courses and speeds upwind and chose one with some roll but no pounding. Downwind, I kept stern-to-waves, staying “in the area” of the patrol, and the radar image was clear except for some clutter at a range up to two to three miles.

The crew went into storm routine. No walking on deck, no meals, no toasts. The “Flats” were down below, and the “tigers” (mostly graduates of Mevo’ot Yam) were up top, manning the wheel and radar shifts. I’d occasionally steer stern-to-waves for a check on unidentified noises or sounds of breakage—always under my watchful eye.

Feeling sorry for us all, I turned to my bag and pulled out some “Twist” snacks and bitter lemon drink. I offered them to the tigers, but they said if they ate, they’d roar into the bucket. So, I stood there munching and sipping, feeling fine. Turns out carbonated drinks and high seas don’t mix well for most people. “Twist” snacks weren’t exactly popular anymore either.

After midnight, a Central command officer came on the radio and asked what was going on. I replied that all was fine. They asked if I was continuing the mission, and I said, I was—with some limitations. They said, “Okay, continue.”

At first light, I saw the sea was starting to calm. At the time of mission end, I set course for Ashdod. The return was with waves off the stern quarter—aside from some pounding, it was a fast sail. The sea kept calming slowly, and Ashdod port came into view. I sped up, expecting to enter the harbor soon.

From the open bridge, I checked the deck to ensure all the secured equipment was still tied down. A glance at the stern gave me the impression that “something was missing.” I asked my deputy what he thought was missing, and after a long look, he said, “The depth charge and its cradle are gone.” I agreed immediately and logged it in the ship’s journal.

We entered the port without incident, despite the high waves. After docking, I reported the situation to the flotilla commander.

It looked like the bolts holding the charge and its cradle had broken, freeing the weight we never thought we’d actually use.

The flotilla commander handled the matter routinely, unaware that somewhere between the decision intersections, a scoundrel was waiting for an opportunity.

Even while still in reserve service, I was told a case file had been opened and that the fact I was the only Navy-flagged vessel at sea that night wouldn’t help me. I realized that the scoundrel hadn’t changed his ways—even as the Navy top Commander, and no longer just Head of the red sea arena.

About three months later, I got a summons to a disciplinary hearing at the Equipment Base in Kastina.

On the day of the hearing, my wife planned to leave for a trip to France with the late Uri Levy’s wife. We met at his house in Ashdod the night before, to celebrate and be closer to the airport (we lived in Be’er Sheva). Aryeh Ruder also came to Uri’s house, and that turned the evening into a reunion—one we couldn’t resist. We went to the beach just next to the house, drinks flowed, stories flew.

We returned home in a daze, and in the morning, I woke up at the neighbor’s house. The women had managed to wake Uri, and he drove them to the airport. I was completely out of it, but I immediately knew I was in trouble. I had a hearing and would show up drunk. A hearing + drunk is not a winning combo. Worst of all, I’d be handing that scoundrel a victory on a silver platter.

I washed up and drove the company’s Susita pickup to the hitchhiking post outside Ashdod.

I got out and asked if anyone had a driver’s license and needed to get to Kastina. No problem.

The soldier drove, and I slept in the truck bed until he woke me up at Kastina. I thanked him and went to the restaurant at the junction for coffee and to wake up.

I showed up at the base on time, and a soldier showed me to the judicial officer’s office.

The officer read the file and asked what happened. I told him about the stormy patrol and how the bolts securing the depth charge tore off. He knew nothing about the sea and asked if the waves in movies were real. I answered that in reality, they’re worse.

He asked if there had been an explosion. I told him the charge didn’t have a fuse, so it’s just sitting on the seabed like a rock.

Then he asked the decisive question: “Tell me, could the charge be used as a flowerpot in the yard? Or a menorah for Hanukkah?”

I wanted to answer that maybe if we stuck a hoe handle in the central tube, we could turn it into a dreidel. But I didn’t want to test his intelligence.

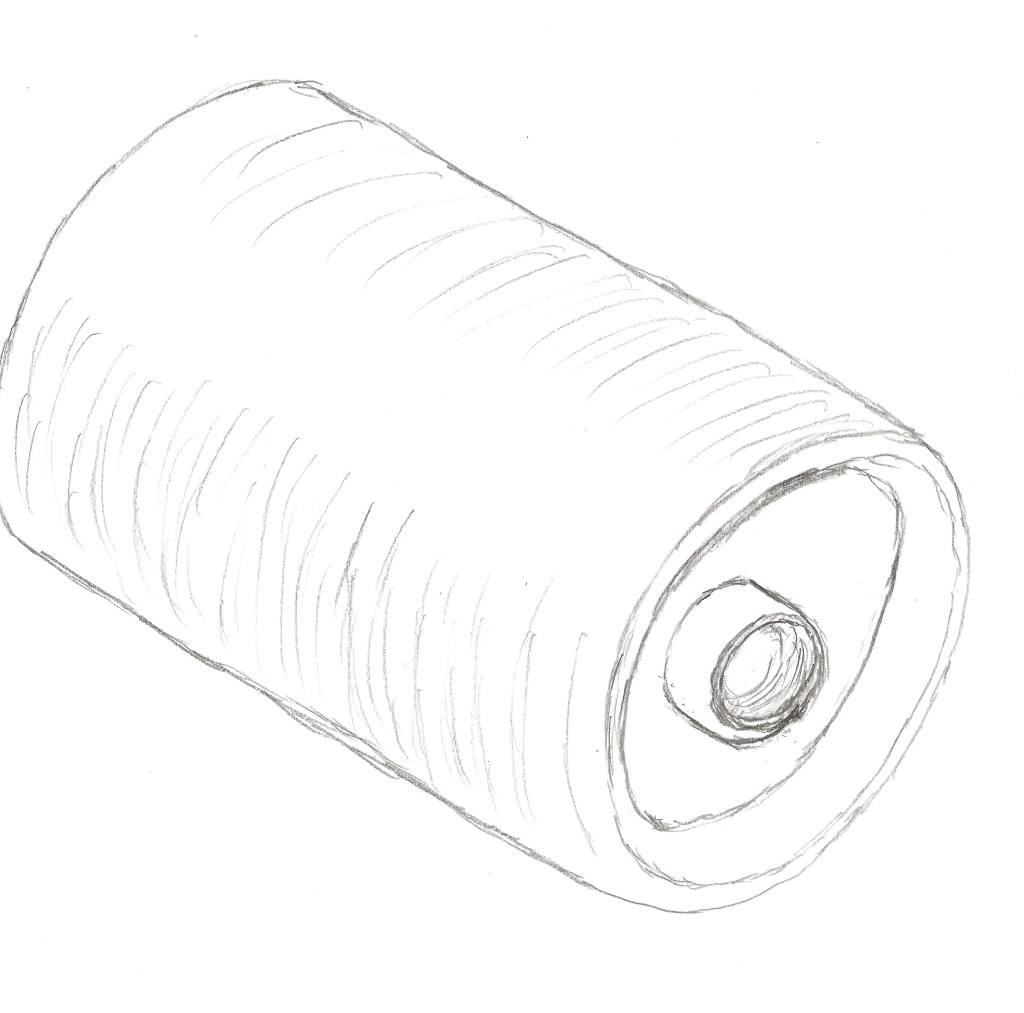

I asked for paper and drew the depth charge in isometric view so he could see it was just a lump…

He looked at me and asked, “So what are you doing here? Why did you even come to me?”

I wanted to answer in one word that would explain everything: “Scoundrel.”

But instead, I made myself small with a gesture and a confused look of “no idea.”

He acquitted me and sent me home.

I felt like a ship with a bow and no stern.

A Depth Charge

Leave a comment