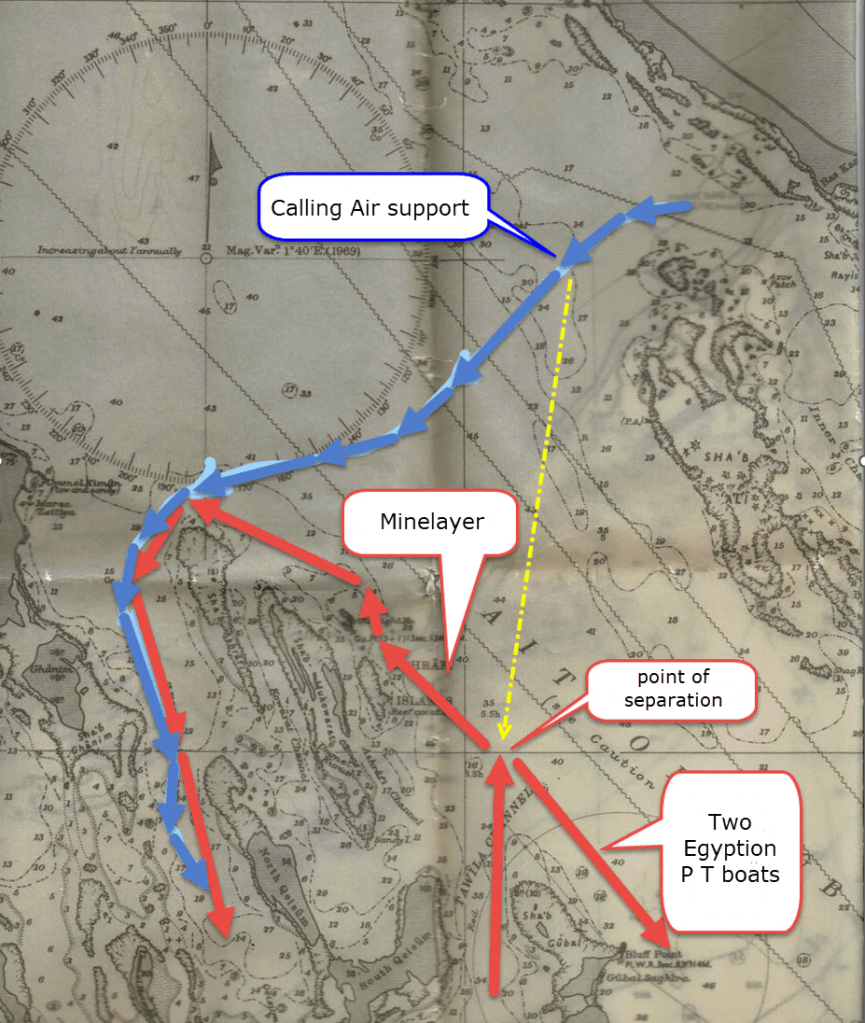

After the war, on Friday afternoon, November 2nd, two boats set out with me leading the pair, to carry out a patrol at the Milan Pass to keep an eye on Egyptian movements at the Yuval Pass and to thwart any mining of the Milan Pass.

I positioned my boat at the northern end of the Milan, and Lt. Kaganovich’s boat was placed at the southern end. At night, about five targets appeared on radar slightly north of Bluff Point, near Sha’ab Jubail. The targets began moving toward Ras Kanisa—basically heading straight toward us. A thought crossed my mind: “I was just at my wedding two nights ago, and my new wife—it’s probably better if she doesn’t know what I’m going through right now.” I requested that patrol boat number two join me, and I reported the situation to headquarters. I immediately received the order: “Go and destroy.”

Boat number two joined me, and together we pushed the throttles all the way to the dashboard and called battle stations. The crew was briefed, and in parallel, we scrambled the air force according to combat protocol (the base in Sharm handled the aircraft launch). The sea was moderately wavy—about a meter high, almost from the stern—which allowed us to travel at full speed with the crew on deck without causing unnecessary discomfort.

As is usual in such situations, radio communication between the boat and the planes initially didn’t work, so the maneuver of “come to me and head toward…” didn’t work. A shame. The instructors from the training base (my boat crew) didn’t practice that like we had in the past—for real—and that was now “biting me in the ass.”

Since the area was small and relatively defined, the planes dropped flares, and the Egyptians began fleeing toward the straits north of Shadwan Island. The aircraft couldn’t spot or identify the targets and returned to base. The targets were moving faster than us, so they gained distance and disappeared south of Shadwan Island—except for one boat that was sailing slowly toward Sha’ab Ashrafi. We understood there was still a chance for contact and continued the chase.

At this point, we realized we were crossing the minefield that the Egyptians had laid during the war and which had caused the sinking of an oil tanker. We hoped, once again, that the relatively small size of the patrol boat and its low draft wouldn’t trigger the mines.

The target approached Ashrafi, and I prayed that the skipper would make a navigational mistake and run aground on the reef. I remember reporting exactly that back. We sailed in total blackout, and the distance slowly closed—but we were still a bit farther than two miles away. The target changed course and safely passed between the reef and the Egyptian coast, and we followed.

The Zaytiah channel, as the area is called, is about 2.5 miles wide at the beginning but narrows as one moves southward.

When the target passed a point southeast of Ras Zaytiah, gunfire was opened at it from the Egyptian coast. We could see the tracers and hoped it would stop them. The shooting ceased after a few volleys, and the darkness (Egyptian darkness) returned to what it was. At some point, when the range closed to about 2,500 yards, we received an order to return to base. We were about half a mile from the Egyptian coast and about eight miles from the northern entrance of the channel, and dawn was approaching.

We returned to base for a very brief and not particularly thorough debriefing (to the best of my memory, conducted by the intelligence officer, Beni). To this day, I still don’t know if they were minelayers, LSTs, or perhaps Komar-class missile boats, which the Egyptians had in the ports of Ardaqah and Safaga. (Now I hear from friends that it was a minelayer, but I didn’t know that at the time—and I have no idea how they know.)

After this incident, things quieted down in the area, and we no longer identified enemy targets in our patrol sector. The gulf once again became ours.

Map

The Minelayer I chased

Leave a comment