Sailing with a Russian is a special kind of experience. A few years ago, I had a sailing buddy, “Matros,” who came from St. Petersburg, Russia, and was rich in experience sailing yachts on the great Lake Ladoga.

He had a boat made by LaCoste (with the crocodile logo), built by a French company based on the plans of a Swan 42. A great boat for cruising, yet still fast.

My friend was a piano tuner by profession, and the rigging on his boat was always tight as the strings he tuned. His boat was named Kamerton—the Russian word for “tuning fork.”

Before leaving from a marina in a landlocked bay on Staten Island, we stopped by a Russian deli and bought provisions for the voyage, as per his instructions. These always included a bottle of fine vodka. He prepared food aboard according to Russian tradition. The food was very tasty, though he wasn’t a cook in the traditional sense. The deli had semi-prepared or fully prepared dishes, and the “chef” had to “combine” them skillfully, heat them up, and serve. There was always Uzbek-style borscht, which I couldn’t stop eating.

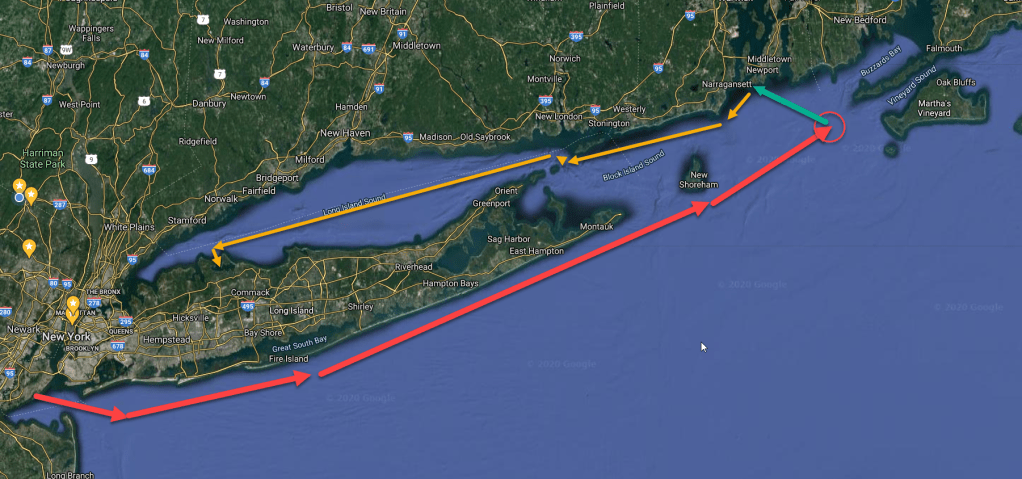

Our voyage track

On a summery morning, we left Staten Island, headed for Martha’s Vineyard. The boat’s enormous keel (2.3m) required great attention while navigating the marina’s channel and the exit route through the bay between the New Jersey and Brooklyn shores—an area full of navigation hazards and shallow spots.

We then sailed in the ocean along the southern coast of Long Island on an ENE course, with an easterly wind. The boat picked up speed in a close haul and handled beautifully at a sharp angle to the wind. My own cruiser would’ve struggled on that angle. Now and then the rail dipped into the water as we sped through the miles in high spirits. The lines were taut like strings, and it was obvious they hadn’t been replaced in a while. I was on edge, waiting for the next line to snap.

Toward evening, the wind dropped, and my friend went below to prepare a light meal before dark.

We sailed all night in a steady breeze. The southern coast of Long Island is pretty dark, and from time to time, you see antenna towers with flashing lights, adding a sense of distance—and thus the feeling of speed.

The whistling wind playing through the shrouds and the rumble of the wake created a quiet melody that accompanied us through the chilly night. Sometimes I wonder if that melody we hear at night is a choir of voices from seafarers lost to the depths, their souls returning to accompany and warn us of lurking dangers with every wave—or maybe just to keep the watchman awake.

By early morning, we could already see Block Island off the port side. A promising sight.

We continued on. When we saw the cliffs of Gay Head on Martha’s Vineyard and, to their left, the chain of Elizabeth Islands, I felt good and looked forward to entering Vineyard Sound.

Then, almost suddenly, the wind dropped and shifted. I was sent to fetch the spinnaker.

The sails on that boat were heavy and bulky, and it was easy for the captain to stand at the helm and call for a sail change. The hard work was up to the crew—and in this case, the crew was just me.

By the time I had the spinnaker ready, the wind died completely, and we were surrounded by calm.

We waited about fifteen minutes to see if the wind would return. When it didn’t, the captain accepted my suggestion to start the engine. I flipped the switch to the starter battery, and my friend turned the key. The engine coughed and died. I went below to be near the engine. On the next attempt, I saw smoke come out of the coughing motor.

We lifted the cover and found that one injector had come loose—the clamp connecting it to the engine body had snapped.

“We are F—ed,” I told him.

He replied with the sentence he always used in tough situations:

“In Russia, it was worse.”

Before the trip, I had asked him if he got towing insurance. In his wisdom, he said there was no need for such insurance on a sailboat—if the engine fails, there are always sails.

Well, now there was no engine, and the sails hung like laundry on a line.

Then came another Russian trait I’d seen before—they don’t use the radio. In Russia, using radios was forbidden. Plus, “the device drains the batteries.”

“Well,” I said, “now we don’t have a choice. We better turn on the weather channel to hear if there’s any wind in the forecast.”

The radio came on (as usual) on Channel 16, and immediately, I heard our boat’s name carried over the airwaves. I paused and heard:

“SECURITE, SECURITE, SECURITE – Coast Guard calling any vessel in the area that has seen a white sailboat with green sail covers named Kamerton.”

I told him we had to respond. He agreed. In our conversation with the Coast Guard, we learned his wife had called them, worried that he hadn’t contacted her. I assured them we were not in danger—though the engine failed, and we had no phone signal. I explained we were waiting for wind and that once near shore, he would call his wife.

From that point on, we had to report our position to the Coast Guard every 15 minutes, which made it hard to focus on handling the boat.

A light breeze picked up, and he turned the bow toward it. Our plan was to return to Newport, where there are mechanics and a big marina that allows easy maneuvering to the mooring ball without a motor. In such a boat, with light wind, you want to maximize apparent wind, so sailing close-hauled, when possible, is best.

As we approached Newport, the wind strengthened. He called his wife to ease her worry, and I got the Coast Guard off our backs. We entered the big marina and asked the Harbormaster for a mooring far from other boats. My friend made a perfect approach to the mooring ball—without an engine. We tied up near the southern tip of Goat Island and began planning the rest of our day.

I found a mechanic who came quickly, diagnosed the problem, and said he’d return the next morning with a replacement injector.

We went ashore, but didn’t eat anything because “there’s food on the boat,” he said. He wouldn’t even buy fresh bread. Back on board, we had to cut moldy spots off the bread leftover from day one.

He went below to cook dinner while I tidied the deck and cockpit.

Dinner was delightful—Uzbek-style borscht and salads, accompanied by romichka (vodka shots). We toasted the boat, the captain, the crew, all sailors everywhere, and… and… Every shot came with selyodochka (pickled/salted fish) and/or ogurchik (pickled cucumber). A true feast for the palate and the gut.

After dinner, we sat in the cockpit, enjoying the darkness, the silence, the fresh air, and the stunning sights of the marina.

Masts on a Mega-Yacht

Eric Clapton’s “Boat”

From our spot, we could see the lights of the bridges leading to Newport, the mansions built by the world’s wealthy, a large fort near the coast, and the New York Yacht Club, which relocated here. Pure beauty. This is the only marina in the area with deep enough water to host mega-yachts with deep keels and tall masts, requiring red lights at various heights to warn aircraft—just like broadcast towers. The mega motor yachts of the rich also come here. On a previous trip, I saw Eric Clapton’s little “boat” (see photo), and once, even Barbara Streisand lounging on a mega yacht that passed close to ours.

As we stood in the cockpit, taking in the peace and quiet, I let out a tremendous fart. A thunderclap shattered the divine calm of the anchorage. Mastheads blushed from yellow to crimson and kissed each other in passion, meteors fell from the sky, and satellites veered off course.

Then, after a brief final chord, the silence returned.

A-michaye (what a relief). I felt complete.

I looked left at my friend and saw a man frozen in shock. The Russian was horrified. Pale as a ghost, he managed to stammer:

“W-what is this? In Russia, not even in p-prison do they do such things.”

Oh boy, I thought. Russia? Prison? All that’s missing now is the KGB.

I realized the engine smoke had finally reached his ears. I immediately switched to damage control mode.

It didn’t help that I explained how, in some cultures, this is considered a gesture of appreciation by the guest for the hearty meal served. In my mind, I cursed that Uzbek who brewed such irresistible borscht—now unstoppable both front and back.

I offered to make peace with another shot of vodka. The offer was accepted.

The next morning, the engine was fixed, and we continued on a long sail through Long Island Sound, aiming to reach Huntington Bay. Why there? Because there’s a Russian deli, and we were out of vodka. Also, we were eating matzah instead of bread.

The entrance to Hantington

We got there after dark, and from Huntington Bay, entered a southern channel leading to the city pier. We arrived near low tide, and I was worried—the depth sounder beeped warnings.

“No worries,” he said. “I’ve been here many times.”

As we approached the pier at a 45-degree angle, the boat stopped dead—no forward, no reverse. The keel dug a trench in the muddy bottom and stuck. “No problem,” he said. “The tide will rise soon, and we’ll do the last 20 meters.”

But there was one issue: a fishing charter with 50 fishermen returned, needing to dock—right where we were stuck.

Yelling, waving arms, shouting for us to move. We waved back— “We ran aground, nothing we can do.”

We tossed a bowline to the pier, and some smiling passersby pulled us to nudge the bow aside to make room. The fishing boat docked bow-first, and the fishermen disembarked without anyone taking an unintended swim.

My friend went to the deli while I tugged the boat’s stern off the ground as the tide came in. When he returned, we were properly tied, and he went below to make a meal to close another adventurous day.

The next morning, we woke to dead calm and falling tide. We realized we had to leave the pier quickly. We exited through the channel to Huntington Bay, dropped anchor, had breakfast, and checked the forecast. Winds were forecasted to be 5–10 knots from the east—perfect for a spinnaker sail all the way to Hell Gate. From there, we’d motor down the East River.

I took out the spinnaker bag and tied it to the bow rail. We raised anchor and headed for Long Island Sound.

Right away, I felt something was off. The easterly wind strengthened the closer we got to the bay’s mouth. I advised the captain to reduce sail before entering the Sound, but he brushed me off:

“In Russia, it was worse.”

In the Sound, we were hit by 25-knot winds with 35-knot gusts. We entered with full mainsail and 130% genoa. The captain needed to sail west but could barely hold a NW course—taking us to Stamford on the other side. In such wind and waves, sailing downwind with that much sail was not an option.

The captain decided to drop the mainsail—without engine assistance. He pointed hard into the wind and sent me to the deck to pull it down and fold it.

For those unfamiliar: Long Island Sound is a narrow 90-mile bay running east-west. An easterly wind blowing overnight kicked up steep two-meter waves that day (fetch, strength, duration).

The boat, close-hauled with full sails in such wind, heeled over so far, the rail was underwater most of the time, slamming into waves. The mainsail sits in a track on the mast and is only easy to drop when head-to-wind. In other angles, friction increases, and it resists coming down. It takes strength to pull it down and fold it. Made of thick Dacron, the sail becomes stiff like plywood. To do this task It takes a crew of three at least.

But the crew? Just me—with a harness clipped periodically to the windward rail.

With great difficulty, soaked with spray, nearly at my limits, I managed to stay on deck while everything around tried to throw me off—and I got the job done. Not before my good cap flew off into the churning water.

Now the steam was coming out of my ears. I was fuming.

A while later, as we calmly sailed downwind with a reefed genoa, I had time to ask him about his decision-making.

Why didn’t we reef before leaving the bay? Why didn’t he start the engine to luff up and drop the main easily? Why does he even stand by the helm when he has an autopilot?

His answer?

“We need to practice.”

Practice for what?! I asked. The Olympics? The Vendée Globe?

In my physical condition, I’m no longer fit to compete in the Wednesday kids’ regattas at the sailing club.

And he just stands by the helm, because his physical condition isn’t great either—and it wasn’t that long ago that I took him to the clinic for a hernia operation.

He probably got the hernia from lifting his sail bags, which weighed more than the pianos he used to tune.

I don’t train anymore. I sail for pleasure. I’m not looking for another half-knot.

As long as the boat is moving forward, I’m happy.

I never sailed with him again. Let him sail with Russians and keep training without me.

Epilogue

About a month later, my friend took part in the annual regatta around Long Island. The regatta is known to be a grueling race, involving sailing through fog, darkness, rain, and shifting winds.

At that time of year, calm winds at night is common. The regatta is very competitive.

Everyone cheats everyone—starting their engines at night, hoping no one from another boat notices.

I refused to join. He brought along a tough crew of former Russians.

Halfway through, they realized someone was missing.

None of them had any idea when it happened.

They continued and completed the race without reporting it to the Coast Guard, as required.

When they arrived at the marina at the end of the race, they found out the guy had fallen into the water, swum to shore, hitched a ride, and made it home.

From home, he contacted them to let them know he was okay.

Since then, I’m no longer sure that it was worse in Russia.

Leave a comment