I met Ido Laderer (a veteran missile boat commander) while searching for a route for a charter sailing trip in the Caribbean—one of the trips organized by Ami Sarel. Ido had spent many years roaming among those islands, so I tried to leverage his vast experience for the mission I was given. When we later met at a sailing club in City Island, I encountered a man who spoke little, ate little, and was rich in seafaring knowledge and experience.

When he invited me to join a voyage from Newport, Rhode Island to Bermuda, I was delighted. Bermuda is a dream destination for every sailor on the U.S. East Coast. A Bluewater Voyage with challenges beyond coastal sailing, represents a true test for anyone who considers themselves a sailor.

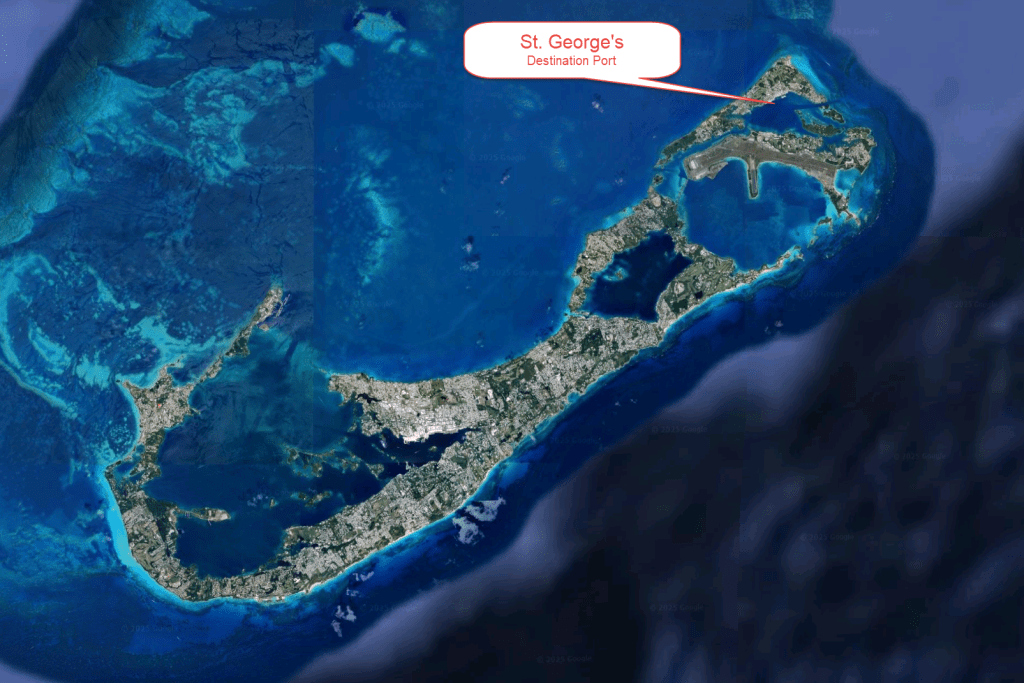

The Island of Bermuda

The sail was scheduled for October 20th, which is close to the end of hurricane season. Two days prior, a hurricane passed far out in the Atlantic from Newport. We planned to depart right after the hurricane moved on towards Nova Scotia, aiming to exploit a weather window between storms—just in case another developed. The forecast for that morning predicted southern winds with swells from the south. The wind was expected to shift to northwest, which would reduce the waves-height and make for smoother sailing.

The boat, a 40-foot Caliber model, built for long-distance voyages, was equipped according to a Spartan philosophy—very little electronics and no luxury gadgets. A GPS was available for positioning, but there was no chartplotter, and the equipment on board was limited to what was strictly necessary to operate the boat, minimizing potential failures. Ido had sailed this boat previously on long voyages, often solo. All necessary gear was ready for immediate use and designed to prevent operational issues for inexperienced guests. In short: “Idiot-proof.”

On Friday evening, October 19th, I arrived in Newport. I found Ido and another crew member, a young man named Lev who was looking to accumulate sea hours toward earning his skipper’s license. It was raining and cold (by late October, temperatures their approach freezing). I took them out for dinner so we could get to know each other better. From there, we took Ido’s dinghy out to the boat, which was moored to a buoy.

Newport, RI Harbor

The next morning, we began final preparations for departure. At one point, we paused for a safety briefing and more detailed information.

First, we crew members signed a document stating we were taking personal responsibility for ourselves. Meaning: if someone fell overboard, they shouldn’t expect the boat to turn back to rescue them. Since only one person would be on watch at a time, discovering a man overboard would likely come too late, and the chance of rescue would be nonexistent. Therefore, in such a case, the boat would continue on its planned route.

We also went over the boat’s routines. Each day, we had one proper meal in the evening before the watch change. At other times, everyone was free to eat from the plentiful supplies on board. A different person would be designated as the cook each day, and that person would also be responsible for cleaning the galley. In the days leading up to the sail, I tried to get out of cooking duty since I hadn’t prepared any food in my all life. I volunteered to be on cleanup duty instead, in exchange for exemption from cooking—but no luck. The logic was that if the cook didn’t clean, they’d dirty every dish, which would waste water—precious on a voyage like this. In the end, I brought frozen home-cooked meals from my wife in a cooler, and everyone enjoyed two delicious meals.

Another routine was wake-up calls. Each crew member was responsible for waking themselves up for their watch. The person on duty would not wake the next in line. This worked well, and no shifts were extended due to negligence. A Casio wristwatch hung in the boat and ticked every half hour, adding a sense of time to the endless dreamscape of the open ocean.

We continued preparing the boat under Ido’s command, who managed everything in an orderly and pre-planned way, with skill gained from previous voyages.

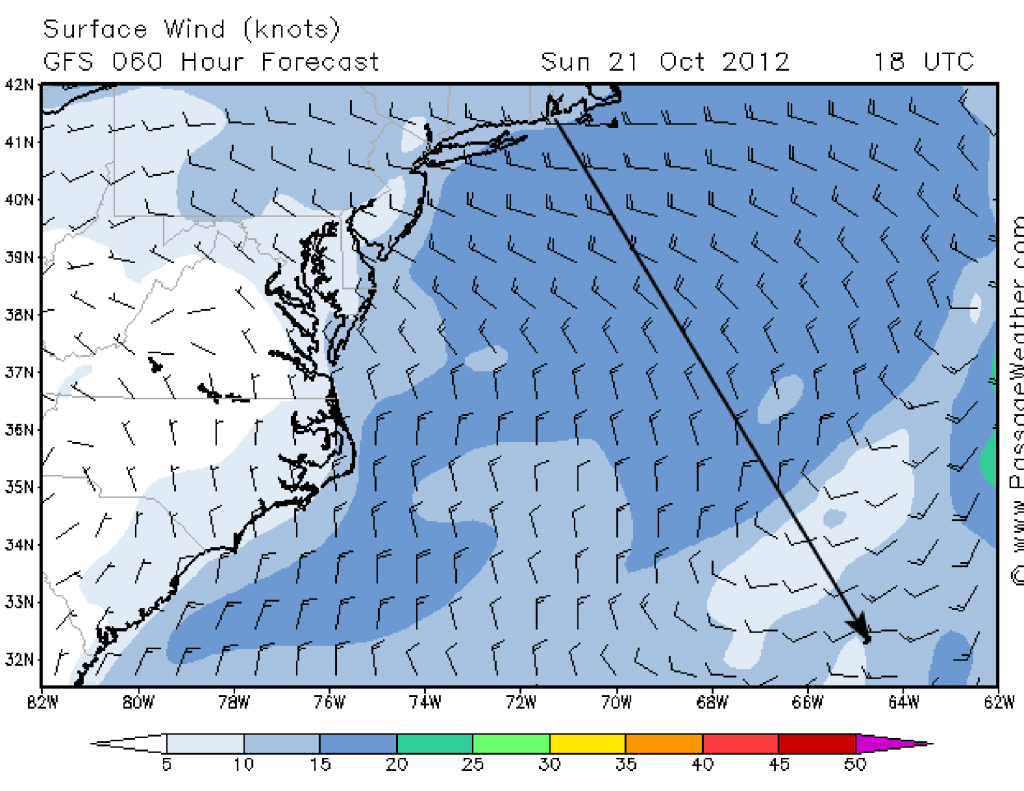

Because the boat’s HF (high-frequency) radio could not operate on amateur radio frequencies, I couldn’t receive real-time weather forecasts from friends. I had to print updated wind and current maps at home for each day, to help plan the route. While at sea, we received weather updates from the U.S. Coast Guard, which broadcasts forecasts regularly. The straight course was 165 magnetic, about 630 nautical miles, though the real route would change based on Gulf Stream currents and wind conditions.

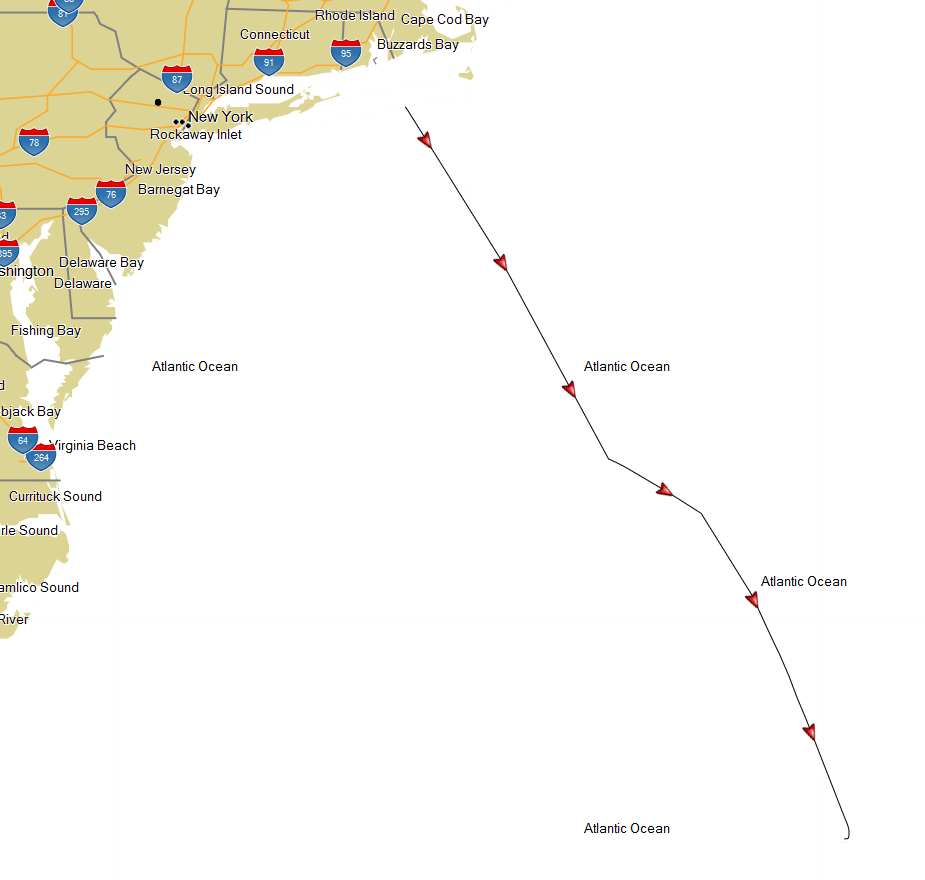

Rhumb line to Bermuda

Map for prediction of wind and seas

Map for prediction of the Gulf stream

The Gulf Stream flows like a river through the ocean from west to east, passing south of Newport, about a day or two’s sail away. It’s recognizable by its color, water temperature, and cloud cover, which appears only above it. Winds over the stream strengthen due to the heat it releases. If easterly winds (opposite the stream’s flow) prevail, the sea becomes steep and rough, making sailing extremely difficult. The Gulf Stream, like all water currents, has side eddies that can either accelerate or slow the boat depending on how the route is planned (see the attached current map). Luckily, the current’s forecast map changes slowly, allowing advance planning. When crossing the stream, the boat also drifts eastward.

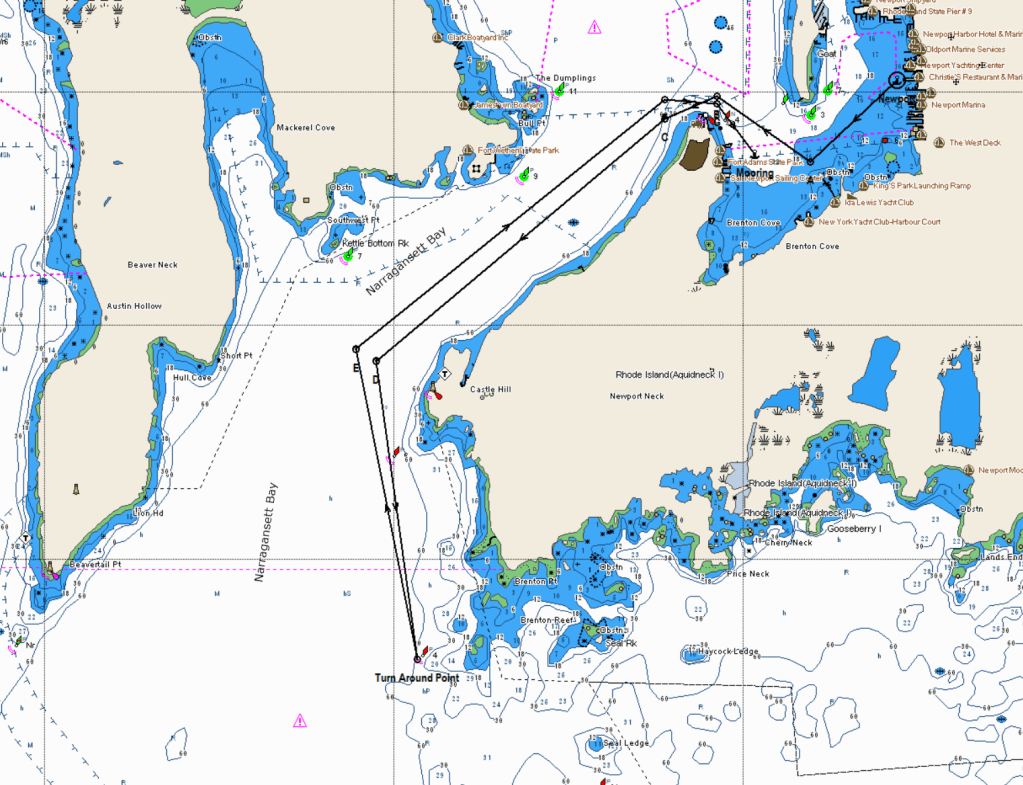

Around 2 PM, we finished preparations after filling the tanks with water from a dockside faucet in Newport. We brought the dinghy aboard, secured it, put on foul-weather gear, untied the lines, and set off for Bermuda. The skies were cloudy, and the wind inside the bay hadn’t shifted yet. Still, we left, hoping the forecasted change had already occurred outside the bay.

While still in Narragansett Bay, on our way to the ocean, Poseidon reminded us who’s boss. The bay was raging. Heavy fog lay on the water, and torrential rain began. To add to the chaos, a large cruise ship was also departing Newport. We hugged the reef markers along the bay’s edge. Channel 16 was busy with travel advisories, and I waited for the skipper’s decision. After a few minutes, we made a U-turn and headed back to Newport harbor.

As the saying goes: “A gentleman doesn’t sail into a storm,” and we were, after all, proper gentlemen.

First attempt to sail out of Newport

We returned to a harbor under fairly clear skies and decided to set out the next morning. I knew of a mooring field near Fort Adams, out of sight of harbor officials, and we tied up for a good night’s sleep.

Sunday morning greeted us with completely different weather. The sun was shining, a light northwest breeze was blowing, and the swell from the south was low—a remnant of the recent storm. We put on our foul-weather gear again and set out to sea. The sail was pleasant. It was a bit cold, but we could sit in the cockpit and enjoy the view of the surrounding islands and coastlines, which gradually faded over the horizon. We sailed south at an average speed of 6.5 knots—quite respectable for a boat of this size. We began taking watch shifts. As the oldest sailor, I chose the 8 to 12 shift. Ido had already selected the 12 to 4 shift.

That evening, I cooked the food I’d brought from home. I managed to burn the couscous meant as a side dish for the roasted chicken, but the unburned portion sufficed and added a pleasant campfire aroma to the meal.

In the early morning, at the end of Ido’s shift, we entered the Gulf Stream. Warmth radiated from beneath the boat and spread through the air, lulling me into a particularly restful sleep.

When I woke up for my shift, I was greeted by a stunning sight—sailing in deep turquoise water, under low clouds typical of the Gulf Stream. It was hot. I happily shed my jacket, foul-weather gear, wool socks, and boots. The wind shifted to north-northwest, and the boat picked up to 8 knots. The mainsail was shadowing the headsail, so Ido, knowing the boat well in various points of sail, decided to lower the mainsail and continue under the genoa, held out with a whisker pole. With foreguy and afterguy in place, the sail and pole held steady against the boat’s rolling motion. We ran at nearly 9 knots, though the rolling was uncomfortable. Inside the boat, we had to grab rails or boat grab bars to avoid being thrown to the sides.

We chased eddies created by the Gulf Stream that would give us an extra speed boost toward Bermuda. We sailed alone across an ocean stretching from horizon to horizon. Aside from a distant merchant ship or two, we were completely alone. The rest of the day passed uneventfully. I must note Ido’s skill in receiving HF weather forecasts broadcast by the U.S. Coast Guard. The signal was weak, but Ido managed to listen and write it down, while I—supposedly the American of the crew—understood barely 10% of it.

We continued sailing under a north-northwest wind that occasionally strengthened or weakened, but otherwise blew consistently from the same direction. With the wind behind us, long-duration winds created especially large following seas. At some point, it was not advisable for the faint of heart to look aft—the swell and cresting wind waves looked like towering mountains. As expected, the boat would rise to the wave crest and then slide down. Looking forward, though, the sea appeared calm. Tired birds blown offshore by the northern U.S. winds landed on the boat, rested a bit, and flew off again. Ido made sure they didn’t enter the cabin and instructed us to keep the hatch screen closed—a precaution he’d already prepared.

On the third day, in high spirits, we enjoyed a proper shower, boosting crew morale. Overall, we were making good progress, and when the boat moves well, the crew is happy. During the day, weather reports started coming in about a serious storm developing near Florida, slowly moving northward. Based on its speed and our position, the storm (Sandy) was expected to reach Bermuda on Saturday. We weren’t particularly worried, since we were on track to reach Bermuda by Thursday.

That night, during my watch, the wind gradually dropped until it died completely. I waited half an hour, changing course now and then to catch a breeze—but nothing.

I woke Ido and updated him. He came up to assess and decided to start the engine. We were within reasonable motoring range of Bermuda. He started the engine and shifted into gear, but we felt terrible vibrations. He tried different settings, but the shaking persisted. Diving at night to check the propeller is dangerous, but we needed to move. I thought for a bit and asked Ido for a chance to run through a sequence of engine commands. He agreed. I started in neutral, increased RPM to verify the engine was fine. It was. Then I went into reverse, gradually increasing RPM. Then I shifted into forward gear quickly—and the shaking stopped. We were back to quiet motoring.

Throughout the voyage south of the Gulf Stream, we passed through fields of floating seaweed. It was impossible to avoid, especially at night. The area is known as the Sargasso Sea, and the plants are called Sargassum. I assumed they had wrapped around the propeller blades. The reverse gear untangled the mess, and the forward motion flung it away.

Calm conditions near Bermuda are common. The area often forms a high-pressure system known as the “Bermuda High,” characterized by light or no winds. Racing yachts try to avoid such regions, but we were allowed to use the engine—so no problem for us.

We motored all night and the next day. On Thursday, around 8 AM, we radioed Bermuda Border Control and, as per protocol, informed them we were 25 miles away.

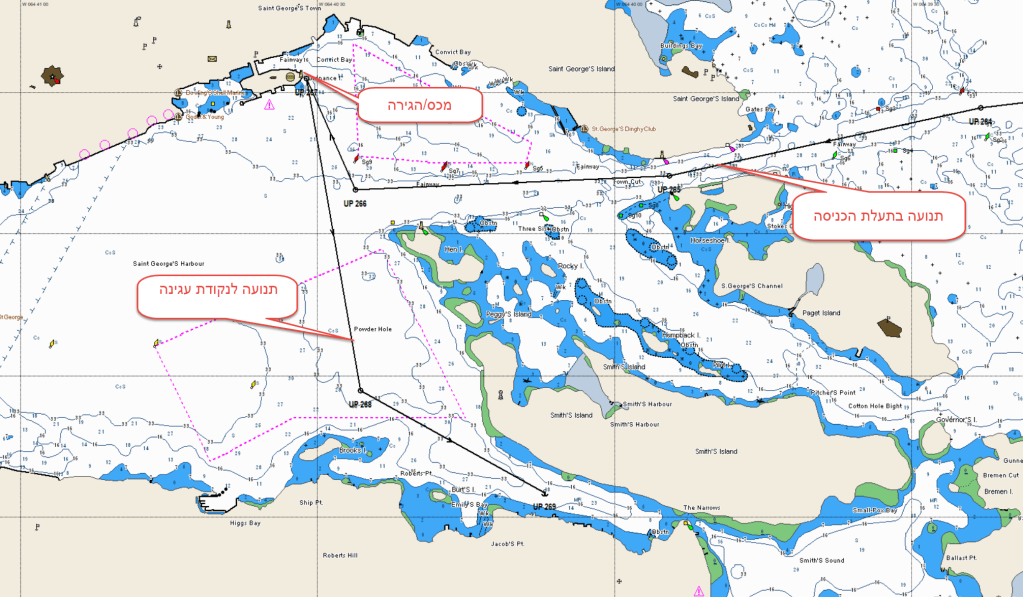

The entrance from Miles buoy to St. George’s Bermuda

There is a formal procedure for sailing to Bermuda to ease entry for sea arrivals. It begins with an email before departure, sent to Bermuda’s Border Police, listing the boat’s name, description, crew members, and estimated arrival date. When within 25 miles of entry, we radio the station with our position and boat name. We continue past markers that indicate the edge of the island’s surrounding reefs. When passing a marker named “Miles,” near the entrance to the channel leading to St. George’s harbor, we must radio the shore station again. This process coordinates passage through the channel, especially if a cruise ship is entering or leaving port.

The island of Bermuda, mostly flat, appears only at short range. The first visible feature is the island’s distinctive white rooftops, which catch the eye. Because there’s little groundwater, rainwater is collected from rooftops, specially designed to channel the water into private underground cistern systems for each home. During hurricanes, strong winds carry sea spray onto the roofs, salting the stored water.

Bermuda on the horizon. See our yellow flag

Crew morale soared as the distance to the island shrank, and more details—ones we had only seen in photos—began to emerge before our eyes.

The channel inward was well-marked and passed close to house back yards. At the end of the channel, an impressive bay appeared, with the customs house and border police on the other side. Since we entered while the station was open to serve incoming vessels, we raised the yellow flag (Q flag) and headed straight to the border police dock. A courteous officer took our ropes and helped us moor.

Saint George’s Harbor

Bermuda Boarder and Custom building on the bow

Ido, who knows the folks there, handled the entry registration himself to avoid having the group’s bad jokes interfere with or delay the process.

From there, we headed to a mooring spot that Ido expertly chose to weather the approaching storm. Ido’s free dive to check the anchor impressed me deeply—his ability to dive to such depth, stay underwater for so long, and all in cold water, was remarkable.

Our actual track to Bermuda

A “Dark and Stormy” (a mix of rum and ginger beer—the signature drink of Bermuda) is a must for all who arrive, and we didn’t skip that tradition.

To sum up, the voyage was fun. The chosen route proved efficient, and we completed the journey in four days and four hours. In a race, that would’ve won us trophies (if we ignore the part, we did on engine power). Kudos to the skipper.

Saint George’s Bay

Friday was spent touring the lovely island.

By Saturday morning, we already felt the first signs of the approaching storm. The skies darkened and a brisk wind began to blow.

Amy (my wife) managed to get me an earlier flight, and I arrived at the airport early. I met other passengers there. We were all worried and hoping the flights wouldn’t be canceled.

The storm moved along the eastern coast of the U.S., but due to its size, its effects reached even Bermuda, which lies about 600 miles from the East Coast.

The planes that managed to leave Bermuda before the storm, including ours, departed on time in the morning, and Amy picked me up from the airport and brought me home before the storm reached New Jersey.

By 2:00 p.m., the wind in our area had picked up, and the power at home went out.

Amy immediately got anxious while I kept smiling and feeling happy.

Amy began unloading the contents of the fridge into coolers and prepared clothes for us to take so we could move into our son’s house, who at the time was traveling in the Philippines with his family. He doesn’t live in the woods like us, and his house still had power.

While she was packing, I sat back and relaxed, floating in a mental space high above the earthly reality. Only her yelling brought me back down to earth, and I started realizing I needed to “switch gears.” Like a bitter awakening from a sweet dream.

“Sandy” was one of the largest storms ever recorded in our area.

The storm passed nearly right over us and wreaked havoc across all the Eastern Seaboard states. The amount of water it pushed from the ocean toward the coast created a tsunami-like wave that flooded all of southern Manhattan and rose up the Hudson River all the way to Albany.

To give a sense of the scale, I’ll mention that my private boat was out of the water at a marina in Haverstraw, about 35 miles north of where the Hudson meets the ocean. That wave reached Haverstraw with a height of about 10 meters (33 feet) above low tide. It destroyed docks and knocked over boats that were out of the water and held by boat stands.

My boat remained upright even though two of its six stands were swept away by the wave.

After the storm passed, we all moved together into damage control and survival mode.

There are those who fear the sea—but sometimes, we should fear more what the land has in store for us. In any case, we must respect and recognize the changes and the power of nature.

Leave a comment